The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) will formally hand over a Book of Remembrance, containing the names of more than 900 previously uncommemorated Sierra Leonean WW1 dead, at an event at the National Museum in Freetown on 22 June.

The book, part of an initiative to honour these men for the first time, will be accepted by Paramount Chief Sheku Amadu Tejan Fasuluku Chairman, National Council of Paramount Chiefs, on behalf of the people of Sierra Leone.

The event will also launch a new exhibition and a nationwide radio campaign to find the families of the WW1 war dead. It is hoped the radio campaign will unearth the stories of those who died, and the public’s views on how these men may be permanently memorialised in the future.

If you are a relative of, or have a connection to a Sierra Leonean who served with the British Armed Forces in World War I, please contact us by Whatsapp on +232 72 218 228

Barry Murphy, CWGC’s Director of Operations elaborated, “The Book of Remembrance provides a temporary place of tribute for more than 900 men of the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps who lost their lives during the First World War (1914–1918).”

“The book will hold their names until a suitable site is identified for their commemoration by a new memorial. The form of that commemoration will be guided by the government and people of Sierra Leone, whose views we are seeking via the nationwide radio campaign.”

“Today, we take a tangible step in honouring those Sierra Leoneans who for far too long, have been overlooked. They were casualties, not just because of the First World War, but of contemporary indifference to their service and suffering. That was wrong then and now, and we, at the CWGC, intend to right that wrong.”

The new memorial will be funded, built and maintained in perpetuity by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The public can share their stories by visiting a new exhibition in the National Museum or via phone or WhatsApp to 072218228.

Mr Murphy added, “No matter where it may be located or what that final design might be, the memorial will deliver a long overdue measure of redress by acknowledging the important role these men played.”

“I would urge anyone who may have a story to tell, to come forward and share it with us. By capturing their stories, and memorialising their names, we will not only honour these men properly for the first time, but we will inspire current and future generations to remember the hugely important role Sierra Leone and her people played in the world wars.”

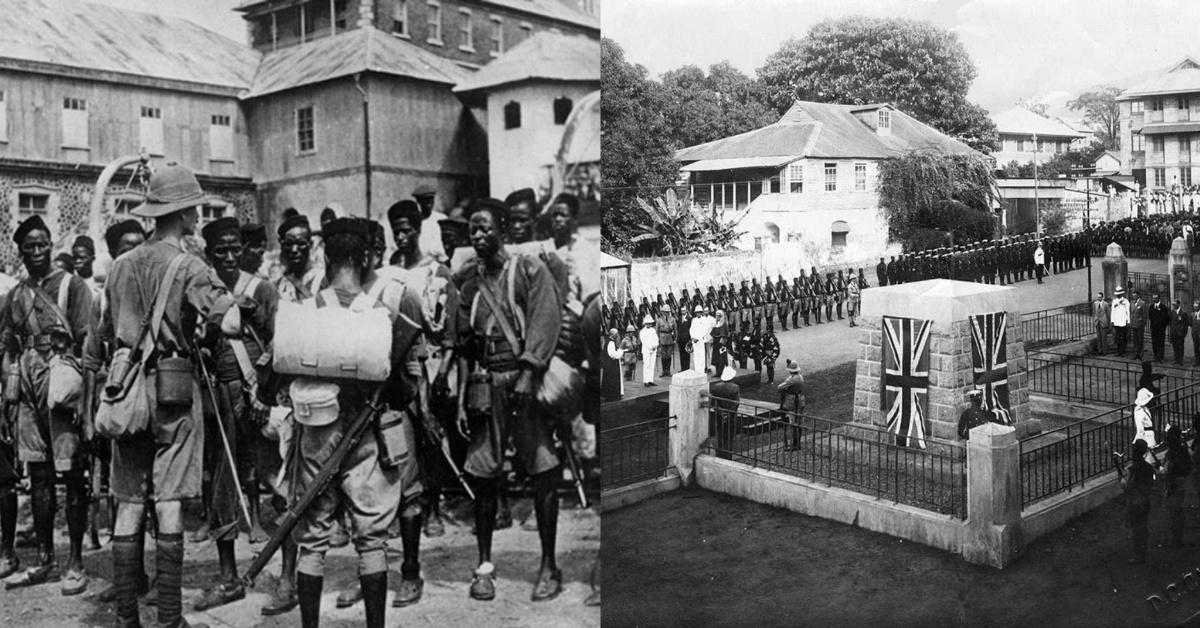

British troops at Freetown, Sierra Leone, leaving for an attack on a German fort at Duala (Douala), Cameroon, west central Africa, during the First World War. Robert Hunt Library/Mary Evans.

This book of remembrance provides the temporary place of commemoration for 939 men of the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps (SLCC) known to have lost their lives during the First World War. During the conflict, many Sierra Leoneans saw service alongside British and imperial forces in the Togoland, Cameroons and Mesopotamia campaigns, both as fighting soldiers and in transport and labouring roles. Most of the men who made up the ranks of the SLCC, however, would support the fighting in East Africa.

While the conflict in Togoland lasted a matter of weeks, the war in the Cameroons would rumble on for two years following British, French and Belgian invasions of the territory in August 1914. However, by far the largest, longest and most costly campaign fought on the continent of Africa during the First World War was that in East Africa. Once fighting in the west of Africa ceased, the manpower this freed up was quickly in demand in the east of the continent where the early years of war had been less successful for British and imperial forces.

In contrast to the war in Europe, East Africa was a mobile conflict fought by relatively small armies over vast distances, making logistics the largest challenge. To make matters worse, a scarcity of rail and road infrastructure limited opportunities to exploit modern mechanical transport, while the tsetse fly and the diseases it spread among pack animals made their use impossible in most areas. As a result, transport through the 750,000 square miles that made up this theatre of war (primarily in what is now Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique) relied on human porterage. Over the course of the war, perhaps more than a million men were raised for these support roles, and in 1916 it took a contingent of 160,000 porters to keep a fighting force of just 27,000 British, Imperial and South African soldiers in the field. These men moved heavy equipment, ammunition and food, and laboured to build the bridges and roads that allowed the army to manoeuvre and fight. These porters – or carriers – quite literally bore the weight of the war in East Africa on their shoulders, and without them the campaign could not have been fought let alone won. Among them was a contingent from Sierra Leone.

As a distinct and titled unit, the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps was established for service in East Africa at the beginning of 1917 when recruiting began through appeals to Chiefs and District Commissioners. Although fighting forces were in demand in this struggle, nothing could be achieved without transport. As the demand for manpower outstripped what was available in the theatre, British West African territories were asked to fill the deficit. Assembled in their respective districts before sailing from Freetown, nearly 5,000 Sierra Leoneans would ultimately travel to East Africa to do carrier service.

Once they arrived in East Africa, the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps saw near continuous service in support of the Gold Coast Regiment and Nigerian Brigade. In the course of its work, the SLCC suffered significant casualties, with many men losing their lives to diseases such as dysentery and tuberculosis. Malaria, however, probably claimed the most lives. While death rates among soldiers from sickness in East Africa in 1917 averaged around 3 to 4 men per thousand per month, the death rate among carrier forces rose from 5 per thousand in January and peaked at 27 per thousand in June before falling to 8 per thousand in November. Although contemporary figures vary, it was thought that at least 850 men who served in the SLCC did not live to see home again.

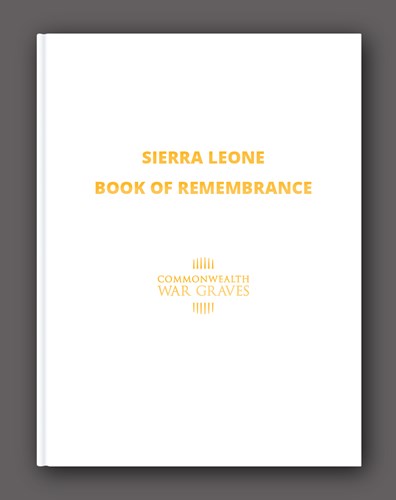

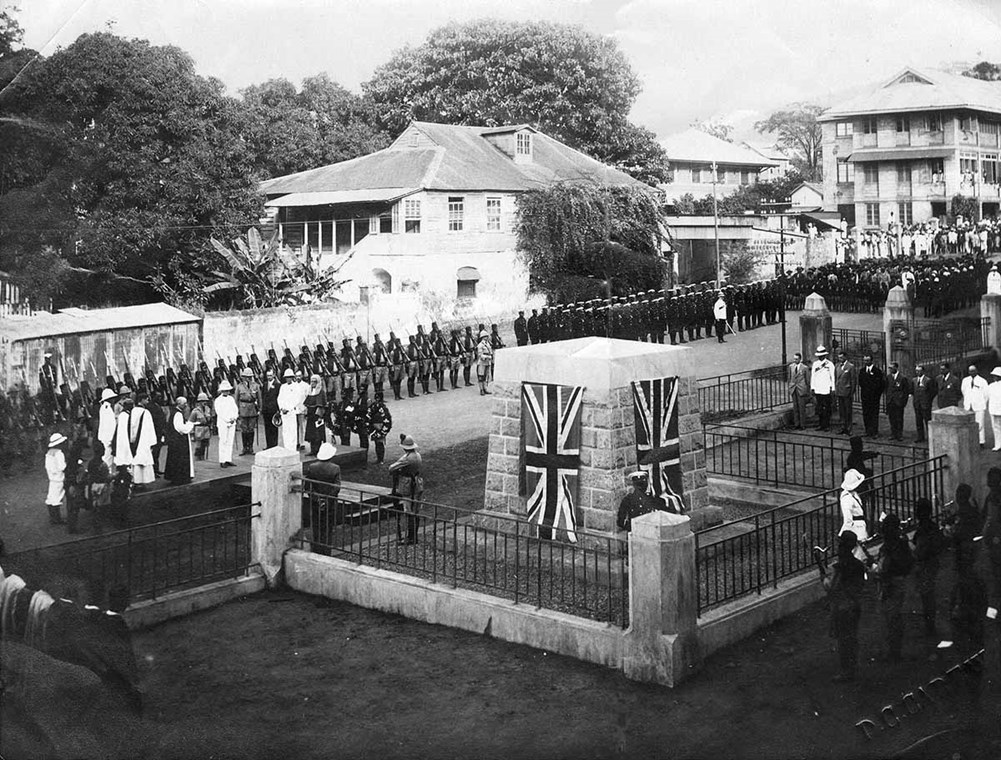

As in all the corners of the world touched by the war, the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) was responsible for the commemoration of the war dead of what was then the British Empire. Discussions over how Sierra Leonean casualties would be commemorated in the aftermath started relatively late. In 1923 the colonial administration established a committee to oversee this work, which in turn liaised with the IWGC. Progress was initially slow, and the registration of graves and the production of cemetery plans within Sierra Leone took several years. By 1926 it was clear that, although they knew the cemeteries in which many Sierra Leoneans had been buried, the nature of their burials meant the graves were unidentifiable. Information from East Africa also suggested most burial locations for these men were unknown. The local committee and IWGC ultimately agreed that a central memorial in Freetown would be the best form of commemoration for all the Sierra Leonean dead, although there was some initial disagreement about the inclusion of names on the memorial.

For several reasons, but principally due to a lack of records, the IWGC had built memorials to the dead in East Africa without inscribing their names upon them. The IWGC expected a similar approach would be adopted in Sierra Leone, but the local committee felt it was appropriate to use names as they were in their possession. Nonetheless, despite this wider decision, it was ultimately agreed that the names of the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps would be excluded as it was believed the communities from which these men came would not appreciate or engage with this form of commemoration. As they also made up the largest losses of any single Sierra Leonean unit, it was also noted that it would be considerably more difficult and expensive to find a way to add their names to the limited space on the memorial.

The final figures commemorated on the memorial included 61 men of the West African Regiment, 55 men of the Sierra Leone Battalion of the West African Frontier Force and 113 men of the Royal Engineers (Inland Water Transport). It omitted the names of 795 Sierra Leoneans known to have lost their lives doing carrier service in East Africa, who were instead remembered in number alone. This same fate was shared by two men originally of the Inland Water Transport and three of the Sierra Leone Medical Corps who had died as part of a contingent en route to Mesopotamia that was seconded at Dar es Salaam to act as carriers. The names of these men were recorded in memorial registers rather than in stone or bronze on the memorial itself.

This commemoration by number remained until after the Second World War, when the design of the memorial panels was altered to include the greater number of casualties from that conflict. As a result of this, all the First World War deaths were confined to a single panel and all trace of the Sierra Leone Carrier Corps was removed, apart from within the Commission’s registers.

This book will hold the names of these men – and any other Sierra Leoneans found to have died during either world war who are as yet not commemorated by the CWGC – until a suitable site is identified for their commemoration. The form of that commemoration will be decided by the people of Sierra Leone.