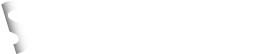

It’s been nearly three decades since Ishmael Beah was recruited as a child soldier during Sierra Leone’s long and brutal civil war, and 15 years since his book about it became an international bestseller.

As a teenager, he left for the US. Now 41, a husband and father of his own children, he has finally moved back to his birth country. In January, he tweeted: “Returning to Sierra Leone almost feels like looking for my voice again.”

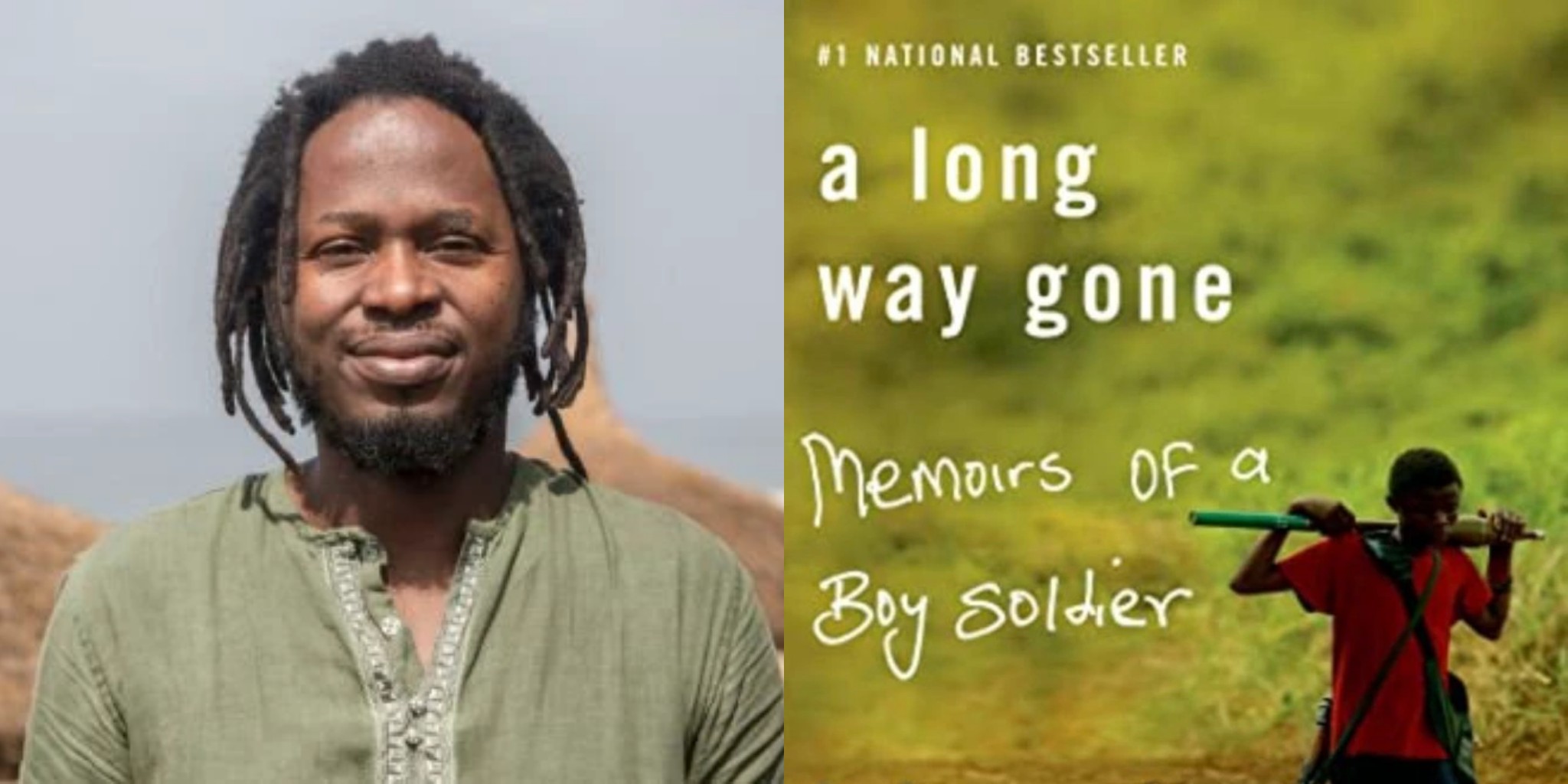

Irish Times reports that, Ishmael has certainly had an extraordinary journey. In A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, Beah documented his life between the ages of 12 and 16, during which he was forcibly recruited into the government’s armed forces, becoming addicted to drugs including marijuana and “brown-brown”, a cocktail of cocaine and gunpowder; watching war movies at night such as First Blood and Commando; and carrying out horrific acts. More than 50,000 people were killed during the west African country’s 11 years of war.

His book also detailed the struggles Beah faced trying to move away from that life, while still just a teenager. Beah spent months in a Unicef-supported demobilisation centre in Freetown, before being asked to make a speech at the United Nations in New York, where he met the woman who became his adoptive mother, whom he later went to live with.

A Long Way Gone, published in his 20s, was an international success: a number one New York Times bestseller; named in Time magazine’s Top 10 Nonfiction Books of 2007; and Amazon’s 100 books to read in a lifetime. It was sold in Starbucks stores in the US, translated into more than 30 languages, and became assigned reading for many school and university students. Beah says he invested in a hat and sunglasses after he began to be recognised in the streets of New York.

Along with fame came inappropriate questions. “So, how many people did you kill?” he recalled being asked during a live broadcast. He told the interviewer he couldn’t remember; that he didn’t write the book to glorify violence. “And then the next time I was introduced as the former child soldier who said he doesn’t remember how many people he killed.”

“I learnt something which is that when it comes to black pain they can rub it in your face,” he says. “If I was not a black, African boy, some of the questions that were being asked of me would not have been asked of me.”

He says he tried to answer with intelligence rather than anger, because he knew if he became angry he would be acting as was “expected” of him. Even today, Beah says he goes to readings and will be told “your English is so good” or asked “do you write your books yourself?”

“They’re not going to believe that I can have intelligence. So intelligence belongs to certain people elsewhere and not us?”

In the aftermath of Beah’s book’s popularity, a team of Australian journalists disputed some of his account, claiming that the attack on his village happened two years later than Beah recorded, meaning he only spent months as a child soldier, rather than years. They said they interviewed locals who remembered Beah living in the village after he said he was recruited. (“You’re a white person coming in saying that this person has made a lot of money . . . You ask them leading questions, they’re desperate . . . They say whatever you want them to say,” Beah responds now.) The journalists also initially claimed that an Australian mining executive working in Sierra Leone had found Beah’s father alive, though that turned out not to be true. (“You know what emotionally that toll was?” Beah says. “Nobody ever asked.”)

Beah says he stopped speaking publicly about the claims after releasing a statement saying that he stood by his book, realising that he only sounded “defensive” when he addressed it further. He wrote everything from the best of his memory, he now says, and of course he didn’t constantly take notes, but that’s because he was living the reality of the situation. He saw this challenge as a disregard for his humanity, despite all that he had been through. “Do people ever go after people who write books from the Holocaust? With Africans, they can rob you and your trauma and then make you pay.”

Shifting world

Beah moved to Freetown from Malibu, California last June. While “there’s never a perfect time . . . I felt like this was the time to come because the world is shifting, whether we like it or not. And if it is shifting, I want to be on the ground so that I can prepare the mindset of my people . . . otherwise, they’ll be left behind again,” he says, drinking coffee at a bar on Lumley Beach, which runs along the western edge of the capital.

Now, he wants to start a “literary revolution”, “nourishing spirits and hearts” with the aim of “decolonising my people from their mindset”. This would involve “not only finding people to write but creating a culture of people who want to read”. In Sierra Leone, “people are interested in the wrong version of famous,” he says – footballers or musicians – but there is not the same respect for intellectual pursuits. Citizens focus on making money because they live in a capitalist society with no safety net, and that constant struggle leaves many feeling bitter and unfulfilled.

“I’m more interested in nourishing the minds of the people because I think this society would only change if people are able to think for themselves deeply and ask questions,” he says. “We are shortsighted in the way we think about our lives because we don’t have the space to think . . . I believe if you teach people how to think they will undo certain things on their own. You know, they will ask certain questions, they will demand more of the leaders of the government.”

He says he’s been gifting copies of his books ad hoc to libraries and coffee shops around the country, and he is keen to start Sierra Leone’s first literary festival, hopefully within the next year.

Another longer-term plan is for a “state-of-the-art library” where there are contemporary books, unlike the dusty old ones that are more likely to be found in schools across the country. “We don’t have a national library in this country. What does it say about how we view knowledge? How do you move a society forward if they’re still reading something from 1960?” he asks.

There would be spaces where black writers who visited the country could give readings; others that could be rented for meetings or exhibitions; a coffee shop that would create jobs. Beah has already bought land and says he can get donations of books from publishers around the world, but he needs private investors to contribute as well. In the meantime, he hopes to begin monthly public discussions on set texts that he will make freely available, and run showcases where young writers can present their work.

Aid industry

Beah is a Unicef goodwill ambassador, but he says he only accepted the role with the understanding that he is also free to criticise the aid industry. And he does.

In Sierra Leone, as elsewhere, the foreign aid industry is colonialist, he says, holding the economy and people back, and making them dependent. “It’s always been like that.” Organisations operating there include Irish ones: Goal, Concern Worldwide and Trócaire. “They’re ingraining it in [Sierra Leoneans] that they’re incapable or they don’t have knowledge, they don’t have wisdom, they can’t do anything for themselves,” Beah says. “There’s no self-sustainability. The programmes they put in place are performative . . . We are trying to develop a middle class in this country. What are [the aid organisations] putting in place for that to happen?”

He says foreign organisations should only be allowed to operate if they hire local Sierra Leoneans or can prove that certain skills do not exist inside the country. They should also have to prove that their work is improving the economy.

He says Africans have “strayed so far from what is within us that we are always looking outside for solutions. And those solutions that are often handed to us are not really what works for us . . . I want to change people so that they can look more to their own traditions and culture, to the arts, to the history, to the storytelling that we have already in us . . . So people see that we have intelligence and creativity and talent here, that we are thinkers here.”

He believes that Sierra Leone is changing today “for the worse”, partially because of the large numbers of people who moved to Freetown during and after the war.

“Everybody is fighting for the same [few] opportunities,” he says. “And also after the war, we did not really talk about our trauma . . . So you have a lot of unresolved issues: behavioural issues, social issues; people don’t know how to be in public spaces with one another.”

He says the war began because of inequality. “A small number of people had so much and a lot of people had nothing. And those disparities still exist.”

Avid readers

Beah is married to French-born Congolese-Iranian human rights lawyer Priscillia Kounkou Hoveyda. Their children are avid readers, he says, which reminds him regularly of the need for them to come across people who look like them in the literature they encounter.

How can people see the intelligence, the brilliance, the art that comes from Sierra Leone without always that undertone of war? Yes,it’s part of our history

In 2014, Beah switched to writing fiction, publishing Radiance of Tomorrow, a novel looking at the aftermath of war. In 2020, he released Little Family, which recounts the lives and ingenuity of street children living in an unnamed developing country that resembles Sierra Leone. He is now working on another memoir, a follow-up to A Long Way Gone.

Through his work, Beah says, he wants to change how people view his country. “Anywhere in the world there are always crises that come and go. But how can people see the intelligence, the brilliance, the art that comes from Sierra Leone without always that undertone of war? Yes,it’s part of our history, we can never undo it. And we should not ignore it.” But at least if Sierra Leoneans are guiding the way they are spoken about, that will make a big difference, Beah believes.

There are other Sierra Leonean writers doing well internationally, including Aminatta Forna and Namina Forna, but Beah says he can often be the only one – or even the only African – who readers he encounters might be aware of. When he agrees to pen something for a literary journal, Beah says, he now stipulates that the editor must commission one or two young Sierra Leonean writers alongside him.

“I cannot write every story there is to write about Sierra Leone, even if I locked myself in a room and write until I’m dead.”

Post a comment

Post a comment

Comment(s)

Disclaimer: Comments expressed here do not reflect the opinions of Sierraloaded or any employee thereof.

Be the first to comment