Implications for the 2023 Presidential Election

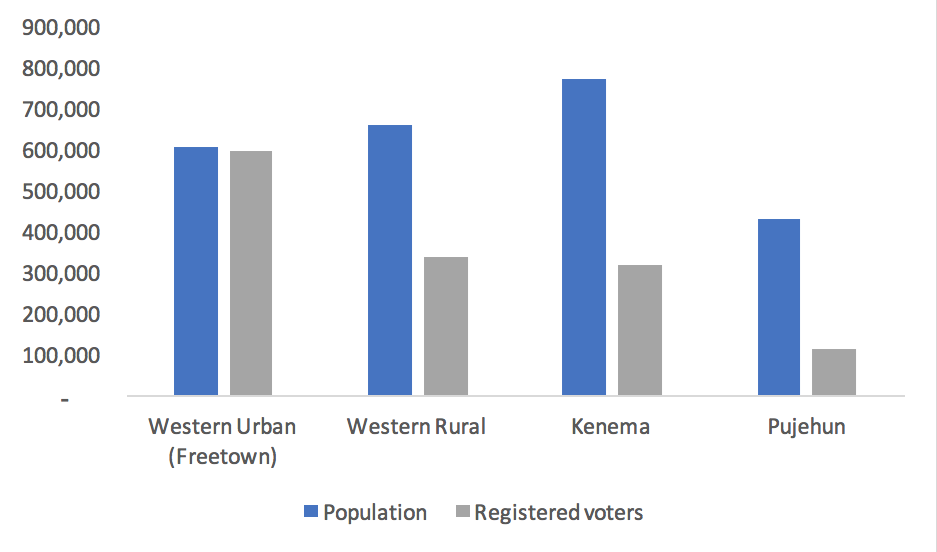

The lopsided ratio of registered voters between the two regional voting blocs has implications for the presidential election scheduled for 24 June. Apart from the presidential election of 2002 in which the Sierra Leone People’s Party’s (SLPP) Ahmad Tejan-Kabbah won 70 percent of the votes, a bipolar ethno-regional cleavage has defined Sierra Leone’s electoral politics since the reintroduction of multi-party politics in 1996. In the run-off presidential election of 2018, 67.3 percent of Maada Bio’s SLPP votes were from the South and East and 89.2 percent of Samura Kamara’s All People’s Congress (APC) votes were from the North and Western Area. This ethno-regional bifurcation explains why census and registered voters data are always closely watched as they give some indication of how parties are likely to fare in presidential elections.

If the ratio of 50.01:49.99 recorded in the 2021 census had been repeated in the voter register, this would have massively boosted the chances of the incumbent president, Maada Bio, to win the 2023 presidential election. A registered voter ratio of 59.19:40.81 between the two voting blocs sends, however, a negative signal to Bio and his ruling party and elevates the main opposition APC’s chances of returning to power.

However, a favourable voter register does not necessarily guarantee electoral success as can be seen from the defeat of the APC in 2018. In that election, the APC lost ground in all the 16 electoral districts. Significantly, its vote share declined in the Western Area from 72 percent in 2012 to 60.5 percent in 2018, and in the North from 88 percent in 2012 to 82 percent in 2018. The National Grand Coalition (NGC), which drew 60 percent of its support from the North (88 percent of its votes were from the North-West), contributed to the six percent decline of the APC’s share of votes in that region. The APC’s vote share in Kono in the East also declined from 58 percent in 2012 to 27.4 percent in 2018.

In “The Humbling of the All People’s Congress: Understanding Sierra Leone’s March 2018 Presidential Run-off Election”, I characterised the APC’s failure to retain power in 2018 as a protest vote against the party. This can be traced to the party’s two region strategy (fielding its standard bearer and running mate from the same voting bloc—North-Western Area); and poor record in office, especially during its second term when the key economic indicators sharply deteriorated and its leader, Ernest Koroma, became an all-powerful and unaccountable president.

Bio on the other hand won the 2018 presidential election on the strength of a four region strategy: maximising his vote share in the six Mende-speaking districts of Bo, Moyamba, Bonthe, Pujehun, Kenema and Kailahun to stratospheric levels (securing an average of 89 percent of the votes in those districts); flipping Kono in the East (which was facilitated by the APC’s expulsion of Sam Sumana, who hails from that district, from the party and as Vice President of the country); and making substantial inroads in the Western Area where he increased his vote share from 25 percent in 2012 to 39.5 percent in 2018. He also almost tripled his vote share in the North, albeit from a low base—from six percent in 2012 to 17.8 percent in 2018.

The two alternations in power that Sierra Leone has experienced after the reintroduction of multiparty rule—in 2007 and 2018—occurred after an incumbent party had served two terms in office. However, this should be seen as largely fortuitous rather than ordained. Tejan-Kabbah secured a second term in 2002 with a 70 percent majority because of the post-war dividend (with the economy signalling a strong rebound and recording the highest ever post-civil war growth in 2002 after the regression of the war years) and his commendable effort in reaching out to the other half of the ethno-regional divide, including in his ministerial appointments. He even secured one third of the votes in the North during the 2002 presidential election. Similarly, Ernest Koroma’s first tenure as president (2007-2012) coincided with a global raw materials boom, which boosted the country’s GDP, helped in the construction of roads and electricity supply and gave the impression of progress. He was rewarded with a 57.8 percent majority in the first round of the 2012 election.

Bio, we should recall, won the 2018 election by a margin of only 3.6 percent or 92,235 votes. A vote swing of only 1.8 percent or 46,118 votes will cause him to lose the 2023 election. In the forthcoming election, he is confronted with serious headwinds, chief among which is the poor state of the economy. Inflation currently stands at 26.81 percent (compared to 16.03 percent in 2018); and food inflation is at a record post-civil war high—registering an astonishing 43 percent in the fourth quarter of 2022. The national currency has depreciated against the dollar almost three fold from Le7,664 in 2018 to Le21,632 in 2023, and the GDP has grown at an average rate of only 2.8 percent between 2018 and 2022—not enough to generate meaningful jobs for the large number of unemployed or underemployed youths trapped in poverty. We do not have poverty data that covers the period 2018-2023 (the World Bank’s most recent value for poverty in Sierra Leone is for 2018). However, a study conducted jointly by the World Food Programme and Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Agriculture in August 2022 found that 81 percent of households were food insecure and 14.9 percent were extremely food insecure (World Food Programme, 2022).

A popular refrain in Freetown on the high cost of living during Bio’s first two years in office was “di gron dry” (literally “the ground is dry”—or times are hard). The new words on the streets are “sufferness” and “sufferation” (or suffering). On the plus side, the government has spent substantial sums of money on its flagship Free Quality School Education programme (accounting for 22 percent of the budget), which has raised enrollment levels tremendously across the country. However, parents are still responsible for about 25 percent of the resources or finances received by schools in the form of levies; non-fee/basic textbooks expenditures–such as on uniforms, bags, food and transportation–are still a burden on households; and many parents prefer to send their children to private schools as they do not consider state-funded free tuition schools good enough.

Bio’s anti-corruption drive has also run out of steam as there does not seem to be much difference between his government and the APC’s, whose corrupt officials he has hounded and tried to discredit. Corruption continues to be the bane of development. Sierra Leone gained three points in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index during the first year of Bio’s administration, moving from 30 points in 2017 and 2018 to 33 points in 2019. However, performance has stalled at 34 points since 2021. A score of 34 out of 100 is still very low. To compound the problem, the well respected and diligent Auditor General, Lara Taylor-Pearce, was arbitrarily suspended in November 2021, a few weeks before the release of the annual audit report for 2020. The report contained damning revelations of fraudulent practices, questionable use of public funds, and systematic failure to comply with established rules and procedures in financial transactions across government ministries and agencies. The Office of the President was implicated in these wrongdoings, which included the falsification of hotel receipts during the President’s travel to Lebanon, double-dipping by staff on the President’s travel team, inaccurate retirement receipts totalling US$110,000 by the State Chief of Protocol and the Personal Assistant to the First Lady (both of whom were asked to refund the money) stemming from the president’s overseas trips, and direct cash payment of US$170,489 (which may expose holders of such a large amount of cash to charges of money laundering) to settle medical bills (Audit Service Sierra Leone, 2021).

Like his predecessor, Ernest Koroma, whose cabinet largely consisted of people from the North-West (81.8 percent in 2007 and 75 percent in 2010), Bio’s appointments to top government jobs have been highly ethno-regional, alienating those who do not trace their origins to the South-East. Even though he campaigned on a four-region strategy in 2018, he has governed in the last five years on a two-region ethnocratic platform. According to an Institute for Governance Reform report in 2018, Beyond Business as Usual: Looking inward to change our story, 58.6 percent of ministerial appointments were held by individuals from the South-East, which accounts for markedly less than 50 percent of the population. The ethno-regional bias worsened over the next two years. A new book by Umu Tejan-Jalloh (2023), The Early Policies of President Maada Bio: My Thoughts and Analysis, shows that by 2021, the South-East accounted for 64 percent of cabinet appointments. Shockingly, 28 (or 90.3%) of the 31 heads of parastatals and core government agencies were people from the South-East. Only one Northerner and two Westerners headed a parastatal or core government agency. The totality of these economic problems and ethnic biases suggests that all is not well in the polity. A survey by Afro Barometer and the Institute for Governance Reform in 2020 found that only 32 percent of Sierra Leoneans believed the country was “going in the right direction”—a 13 point drop from 45 percent in 2018. Disturbingly, there was a stark divide in opinion by respondents in the two ethno-regional blocs: 14 percent of respondents in the North and 16 percent of those in the West believed that the country was moving in the wrong direction—against 57 percent of respondents in the South and 53 percent of those in the East who believed the country was on the right track.

Given Bio’s small margin of victory in 2018 and the current unfavourable voter registration ratio between the two regional blocs, one would have expected a more inclusive policy in top level appointments, similar to that of Tejan-Kabbah, in order to improve his prospects of re-election in June 2023. As I showed in the article “The Humbling of the All People’s Congress: Understanding Sierra Leone’s March 2018 Presidential Run-off Election”, Bio would not have won the 2018 election without support from voters in the North. Let me quote that section of the article to illustrate the point:

“Relying on the South and East would have given him only 34.85 percent of the votes; and including the Western Area would have raised his vote share to 46.32 percent. It is only when his votes in the North are added that he is able to get to the 50 percent+1 mark. The interesting point about Bio’s Northern votes is that reliance on only his votes in the districts with strong minority presence (Kambia, Koinadugu, Falaba and Karene) would have given him only 2.92 extra percentage points, which would have raised his overall vote share to 49.24 percent. He needed his votes in the predominantly Themneh-speaking districts of Port Loko, Tonkolili and Bombali (which gave him 2.57 extra percentage points) to get him across the victory line.”

Bio’s governance record is also not very different from Koroma’s in terms of how key state institutions, such as the police and judiciary, serve the interests of the party in government. In 2018, just a few months after the elections, the judiciary upheld the SLPP’s petitions against some APC parliamentarians and created 10 SLPP members of parliament who lost the election to those APC parliamentarians in constituencies that were strongly pro-APC. This produced a spurious parity in parliamentary representation between the two parties. The judiciary has also played an activist role in the affairs of the APC: slamming the party with several injunctions, dissolving its national executive, constituting an interim transitional governing committee and dictating the category of people that should be nominated into it. The most bizarre injunction was the one granted to an aggrieved member of the party on the eve of the party’s convention to elect its standard bearer on 17 February 2023 after the court had previously given the greenlight for the convention. There were fears that the APC would not be allowed to field a candidate for the presidential election. Western donors met with the judiciary, the electoral commission, and representatives of the government in an Election Steering Committee meeting on 17 February (EU in Sierra Leone, 2023). The judge reversed her decision on the same day after the Election Steering Committee meeting and the convention was held on 18 February.

Basic freedoms, such as the rights of free speech, assembly and movement are still fairly respected. Bio’s government repealed the obnoxious criminal libel and seditious law (Part V of the Public Order Act of 1965) in 2020, which improved the country’s scores on the World Press Freedom Index from 69.72 in 2020 to 70.39 in 2021 and 71.03 in 2022 and moved up the global ranking from 85 to 75 and 46 respectively, out of 180 countries. However, like many countries that are experiencing democratic backsliding or incomplete democratisation, these freedoms are not well protected and are periodically abused. Police high-handedness and targeted harassment or assault of journalists continue—such as against Standard Times journalist, Fayia Amara Fayia (who was beaten up by soldiers in Kenema); Salieu Tejan Jalloh, editor of The Times newspaper (who was forced to flee the country after being charged of defamation for an unpublished story); and the editor of the US-based Africanist Press, Chernoh Alpha Bah, who has received death threats (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2022) for his hard-hitting investigative work on corruption by government officials in Sierra Leone. The Media Foundation for West Africa (2022), a press freedom watchdog, recently concluded that “the state of press freedom remains an admixture of the good, the bad and the ugly”. Arbitrary arrests, refusal of permits for public demonstrations, detentions, unlawful killings, and use of excessive force against civilians and those considered as anti-government activists persist. Many of these infractions and abuses are documented in the US State Department’s 2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and Amnesty International’s 2023 report on excessive use of force by Sierra Leone’s security forces in 2022.

These shortcomings in human rights or freedoms may explain why Sierra Leone and other countries with similar experiences are not listed as democracies in The Economist’s Democracy Index (2022). These countries are classified instead as “hybrid regimes”–one level above the category of “authoritarian regimes” but two levels below the categories of “full democracies” and “flawed democracies”. Sierra Leone is also listed as “partly free” in Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index (2022). These global indexes are, of course, not perfect because many of the issues they measure and categories for ranking countries require subjective evaluation. However, they are widely consulted by the general public and exert pressure on states to improve governance practices.

A worrying development is the use of violence by the two main parties in pursuing political objectives. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project’s data (2020) show that the number of violent incidents has risen dramatically–from an average of two events a month before 2017 to 20 in the election year of 2018 and has stayed at a very high level. The spike in violence was expected to dip after the election, as happens in many countries. However, between September 2018 and 2020, there were 10 events of political violence every month, with occasional peaks of almost 30 events. Clashes between parties, internal party violence, and targeted violence at civilians or political party agents and supporters have all increased in recent years. It is not surprising that Sierra Leone dropped 15 places in the Global Peace Index from 35 in 2018 to 50 in 2022. Fears of an upsurge in electoral violence have been cited by the Political Parties Registration Commission (2023) as the reason for its controversial decision on 3 April, 2023 to ban political rallies during the election campaign period.

Conclusion

Sierra Leoneans seem to be stuck with the SLPP and APC, which have governed the country since independence in 1961, even though none of these parties have been able to move the needle on development and improve the lives of citizens in any substantive way. Unfortunately for voters, the party that promised an alternative, the NGC, is in its death throes after its leader, Kandeh Yumkella, called for a “strategic partnership” with the ruling party and struck a so-called “progressive alliance” with it on 14 April, 2023. Even well before its fracturing in January 2023, the NGC had become a poor shadow of its 2018 version that secured 6.86 percent of the national vote and four parliamentary seats in Kambia. It may well end up as a small ethnic minority party if it contests the June elections separately or in alliance with the SLPP. The merger or alliance of the NGC and SLPP reminds me of the joke during the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s that “socialism is the longest route to capitalism”. It is now clear that for all its talk about offering Sierra Leoneans an alternative governance and development path, the NGC is, essentially, the longest route to membership of the SLPP.

The demise of the NGC as an electoral force will make it easier for one of the two main parties to win the June presidential election in the first round of voting. The other minor parties, such as the Coalition for Change, the Alliance Democratic Party, the People’s Movement for Democratic Change, the Revolutionary United Front Party, the United National People’s Party, the Citizens Democratic Party, the United Democratic Movement and the Unity Party that accounted for 7.2 percent of the votes in the 2018 presidential election seem to have fizzled out or lack traction. If the APC wins the election, it will not be because it has put up a robust opposition in the last five years or advanced credible policies that will transform the economy or improve the governance regime. The 2023 presidential election is instead likely to be a referendum on Bio’s economic development and governance record—just as Bio’s victory in 2018 was a referendum on Koroma’s record.

The instinct for winner-takes all outcomes and lack of a civic culture in terms of how parties behave in and out of office make the forthcoming elections perilous. Leaders and supporters of the incumbent party, who talk about an existential threat if they lose the election, may seek to cling to power; those of the main opposition party, who are equally determined to win back power, complain about targeted harassments and raise the spectre of revenge if they get back into office. This kind of atmosphere is unlikely to guarantee free and fair elections. There is a real danger of voter suppression, targeted violence and falsification of results. When will Sierra Leone get its act together and rise above the politics of “yu du mi, ar du yu” or tit for tat?

References

Afro Barometer and Institute for Governance Reform 2020, Di gron still dry: Sierra Leoneans increasingly concerned about the economy. Dispatch No. 384. 19 August. https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ad384-sierra_leoneans_increasingly_concerned_about_the_economy-afrobarometer_dispatch-19aug20.pdf

Amnesty International 2023, “Sierra Leone: Seven months after August’s protests which turned violent in some locations, no justice yet for those injured or the families of those killed”. March 20.https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/03/sierra-leone-seven-months-after-augusts-protests-which-turned-violent-in-some-locations-no-justice-yet-for-those-injured-or-the-families-of-those-killed/#:~:text=Amnesty%20International%20collected%20testimonies%20alleging,including%20at%20least%20two%20women.

Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project 2020, “Explaining Rising Levels of Political Violence in Sierra Leone”. https://www.jstor.org/publisher/acledp

Audit Service Sierra Leone, 2021, Annual Report on the Account of Sierra Leone, 2020. December.

Bangura, Y. 2022, “Provisional Results of Sierra Leone’s Mid-Term Census: Rebuilding trust will be difficult”, Sierra Leone Telegraph. June 3. Also published as “My quick take on the provisional results of the 2021 mid-term census results”, in Awoko. 6 June, 2022.

Bangura, Y. 2018, Bangura, Y, 2022, “The Humbling of the All People’s Congress: Understanding Sierra Leone’s March 2018 Presidential Run-off Election”. CODESRIA Bulletin. No. 2. Also published as “Sierra Leone’s 2018 Elections: the Humbling of the All People’s Congress”, Premium Times. April 19.

Bangura, Y. 2015, “Lopsided Bipolarity: Lessons from the 2012 Elections”, in Y. Bangura, Development, Democracy and Cohesion: Critical Essays with Insights on Sierra Leone and wider Africa Contexts. Freetown: Sierra Leonean Writers Series. Pp.

Committee to Protect Journalists 2022, “Sierra Leone publisher Chernoh Alpha Bah threatened with death, charges of treason”. May 31. https://cpj.org/2022/05/sierra-leone-publisher-chernoh-alpha-bah-threatened-with-death-charges-of-treason/

Electoral Commission for Sierra Leone, 2022, “Final Voter Registration Figures”. December 24.https://ec.gov.sl/2022/12/24/final-voter-registration-figure/

EU in Sierra Lone twitter page, 2023, 17 February. https://twitter.com/euinsierraleone?lang=en

Freedom House, 2022, Freedom in the World 2022: The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/FIW_2022_PDF_Booklet_Digital_Final_Web.pdf

Institute for Governance Reform’s 2018, Beyond Business as Usual: Looking inward to change our story. October.http://igrsl.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/PDF-IGR-Critical-Perspective-Looking-Inward-for-Change-our-Story.pdf

Laporte, P. 2021, (World Bank Country Director Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone, Africa West and Central Region), Letter to Sierra Leone’s Minister of Finance and Economic Development. 7 December.

Media Foundation for West Africa 2022, “Sierra Leone’s press freedom situation: The good, the bad and the ugly”. December 21. https://www.mfwa.org/sierra-leones-press-freedom-situation-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/

Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, Annual School Census Report, March 2021. https://www.dsti.gov.sl/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ASC-2020-Report.pdf

Political Parties Regulation Commission 2023, “Press Release”. 3 April.

Sierraloaded 2021, “Mayor of Freetown Yvonne Aki-Sawyer Reacts to Census Results”. Covered part of the statement of the Statistician General on the launch of the Census report. https://sierraloaded.sl/news/yvonne-aki-sawyerr-reacts-census-results/

Statistics Sierra Leone, 31 May, 2022, Provisional Results: 2021 Mid-Term Population and Housing Census (2021 MTPHC)”. https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/Census/MTPHC_Provisional_Results/2021_MTPHC_Provisional_Results.pdf

Statistics Sierra Leone, 2015, 2015 Population and Housing Census. Summary of Final Results.https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/final-results_-2015_population_and_housing_census.pdf

Statistics Sierra Leone, Final Results: 2004 Population and Housing Census. http://www.sierra-leone.org/Census/ssl_final_results.pdf

Tejan-Jalloh, U. 2023, The Early Policies of President Maada Bio: My Thoughts and Analysis. Will be available on Amazon.

The Economist, Democracy Index 2022.

The Sierra Leone Telegraph, December 9, 2021, “World Bank withdraws support for President Bio’s highly politicised mid-term census”.

The Sierra Leone Telegraph, 10 June, 2022, “Mayor of Freetown writes to Statistics Sierra Leone about serious errors in the 2021 census figures”.

Transparency International 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, Corruption Perceptions Index.

US State Department 2022, “2022 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Sierra Leone”.https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/sierra-leone

World Food Programme 2022, “WFP Sierra Leone Country Brief”. October. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000144976/download/