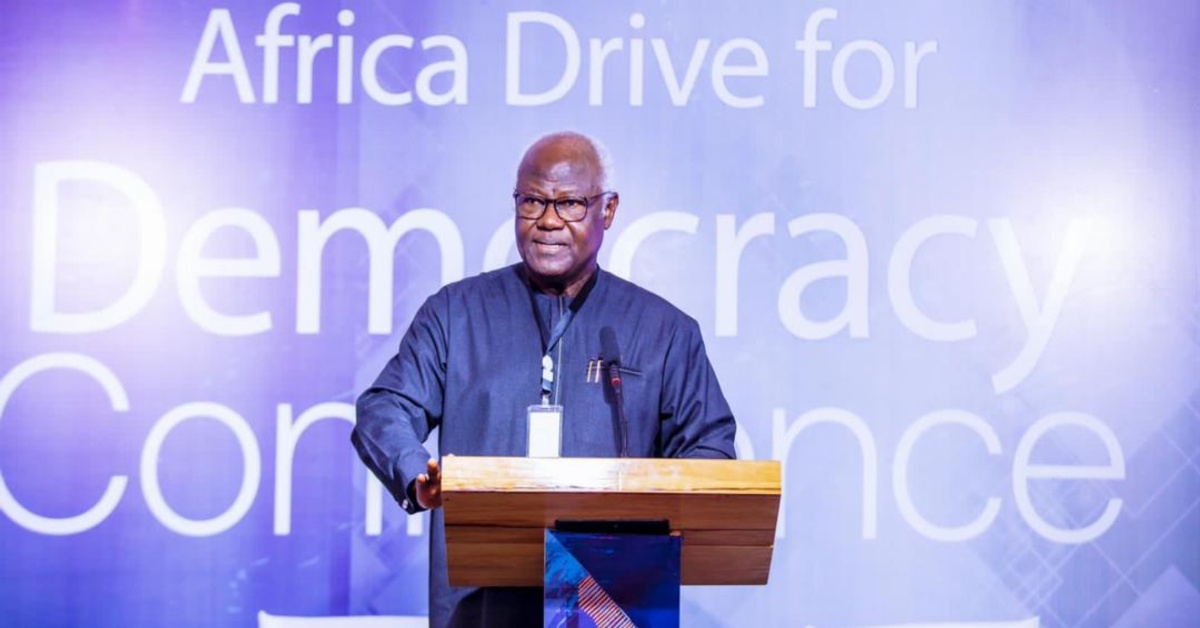

PSC Report asked HE Ernest Bai Koroma, former Sierra Leone president and Head of the ECOWAS Election Observation Mission in Nigeria, what his reading of continental democracy is, given his involvement in election issues as a former president and elder statesman.

Indeed, I have undertaken seven election observation missions at the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the West African Elders Forum; the most recent being the ECOWAS Observation Mission in the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

Impressions have been similar: democracy currently faces challenges globally, including in Africa with the pandemic having disrupted previous gains. Reputable regional and international organisations that monitor trends agree that, over the last decade or two, democracy has declined globally. Among the reasons are the rise in authoritarian rule evident in the rise of unconstitutional changes of government (UCGs), disinformation and misinformation through ‘new’ media (fake news, social media and propaganda) and the perception of corruption at all levels of state governance.

Manipulation of new media is causing mistrust between incumbents and main political parties and, finally, disputed election results, leading to violence. All these issues are linked in one way or another to the democratic governance deficit, as was the case in Zambia, Togo, Benin and Kenya before their recent elections. This is definitely a worrying trend that should be of the utmost concern to anyone who professes to be a democrat.

However, while the current picture of Africa’s democracy trajectory looks somewhat gloomy, it is far better than what occurred 20 to 30 years ago. Then most African countries experienced rampant political instability, civil wars, irregular, unfree and unfair conduct of elections, and lack of political pluralism, among other issues.

While Africa’s democracy trajectory looks somewhat gloomy, it is far better than in the past

For instance, holding regular elections based on constitutionally stipulated intervals is no longer disputed. Even more reassuring is that the decline in African democracy has become the preoccupation of many associations, institutions and like-minded leaders. More citizens are now engaged in governance and democratic processes evidenced by the plethora of local, national and regional civil society organisations. Continental organisations such as ECOWAS and the AU have developed normative frameworks and principles to deepen democratic governance and ensure African peace, security and stability.

Despite the challenges posed by state sovereignty, these organisations are no longer indifferent to what happens in African member states. Thus, I see the continent’s democracy journey as neither linear nor smooth but, in view of concerted national, regional and continental efforts for reforms, there is room for democratic optimism!

What do you see as the main drivers of election-related violence and how can issues be addressed?

While electoral violence has recurred in some African states, the phenomenon is declining, particularly in scale and consequences. The root causes remain the steady accumulation of discontent over economic hardship, and deepening social divisions along ethno-regional, religious and class systems, compounded by the marginalisation of the continent’s youth and women.

The eruption of electoral violence in some African countries may be seen largely as a manifestation of much deeper democracy deficit issues. These include weaknesses in the governance of elections, the practice of ‘winner takes all’, and non-adherence to the rules of orderly political competition.

The AU has developed mechanisms and strategies to prevent and mitigate outbreaks of electoral violence in its member states. These measures include regional and continental early warning systems, appointing eminent personalities such as the Panel of the Wise to mediate disputes, and integrating preventive diplomacy with traditional election observation missions. In Nigeria, the mission started consultations and preparations approximately six months prior to the elections and engaged various stakeholders including political parties, Independent National Electoral Commission, security agencies, and the judiciary, capacitating these actors to be free and fair in their conduct of elections. Now with the conclusion of the vote, we continue to emphasise to all stakeholders the imperativeness of an acceptable outcome and a smooth peaceful transition.

The eruption of electoral violence may be a manifestation of much deeper democracy deficit issues

These moves have, to some extent, hampered electoral violence, notably AU preventive diplomacy in Zambia and The Gambia in 2021, Kenya in 2022, and now in Nigeria in 2023. However, they do not necessarily address the causes. Nor are they aligned with the electoral cycle long term. I believe sound security engagement, effective electoral governance, greater civic engagement, demands for accountability, fostering political pluralism (or pluralistic society) and political tolerance hold the most promise for preventing election violence in Africa.

What lessons were learnt from your involvement in preventive diplomacy?

Each mission and country is different, but one commonality is the considerable mistrust between incumbents and opposition parties. This has made political contestation extremely adversarial. The driver of such animosity is a lack of tolerance for dissent and poor election management. It manifests through the quest for a second term or endeavours supporting preferred successors of outgoing leaders.

Failure to engender consensus on changes to electoral laws, especially when they are made late in the electoral cycle, has also created deep suspicion and resistance. Transparency or the lack of it in voter registration and processes leading to the final voter register are key sticking points.

Mistrust and antagonism are usually heightened by the use of state security to harass, intimidate, arrest and even detain opposition leaders and supporters. By the same token, institutions such as the judiciary and Parliament tend to aid and abet rather than check executive overzealousness, thereby contributing significantly to stakeholder disharmony with electoral processes. This bellicose posture by incumbents often results in their resistance to relinquishing power for fear of reprisals.

Preventive diplomacy helps a great deal when parties are engaged in good time, away from the public glare

Ultimately, it is instructive not to wait until disagreements deteriorate into conflict. Pre-election missions by regional economic communities (RECs) and the AU tend to restrain especially key players and amplify the voices and strength of local actors. Nigeria is a case in point. They also help in early identification of existing challenges, dynamics, actors and influencers. Overall, preventive diplomacy helps a great deal when parties are engaged in good time and away from the public glare, fears are allayed and assurances are guaranteed by mediators.

What lessons can you share as a former president to help the AU and RECs manage governance deficits that could be a major driver of insecurity in Africa?

Organisations such as the AU and RECs can address the primary challenges by:

- Toning down the rhetoric and increasing pragmatic discussion with member states on the values of democracy, for instance, through active preventive diplomacy.

- Focusing on the supply side of democratic governance (that is, ensuring democratic dividend). This will increase popular confidence in the meaning and merits of democratic governance.

- Engendering political pluralism, competition, tolerance and peace among diverse political actors in member states, for instance, through the development or creation of national, regional and continental platforms for political parties and related institutions.

- Increasing efforts to manage diversity on the continent and minimising the political exploitation of ethnic and regional differences among citizens.

- Focusing on building or strengthening the effectiveness of governance institutions and minimising personalisation of politics.

- Stemming corruption, vote buying and other actions for short-term material gratification in the quest for public office.

- Promoting the role of civil society groups and other non-governmental organisations to sustain the growing demand for accountability and responsive governance.

What is your key message to African leaders to create a more secure, stable and prosperous Africa?

This ideal depends on all working in unity. There is a very good life after the presidency but it depends on how well you served your people. I would not have had this platform had I not governed democratically, respected my country’s laws on term limit and served my country to the appreciation of most of my compatriots.

A key responsibility for every leader is to ensure peace prevails in his or her country. That requires maintaining a work relationship with the main opposition, civil society and the media, respecting their views and giving them space to operate and participate in democracy.

Deliberate efforts to suppress opposition parties and independent voices are a recipe for political confrontation and tension. National institutions such as the police, the army, the judiciary, Parliament and election management bodies must be allowed to function independently. This will engender public trust and encourage the private sector to flourish, which, in turn, will boost economic growth. No country grows amid chaos and political instability. Working for national peace, stability and prosperity brings individual peace.

Post a comment

Post a comment