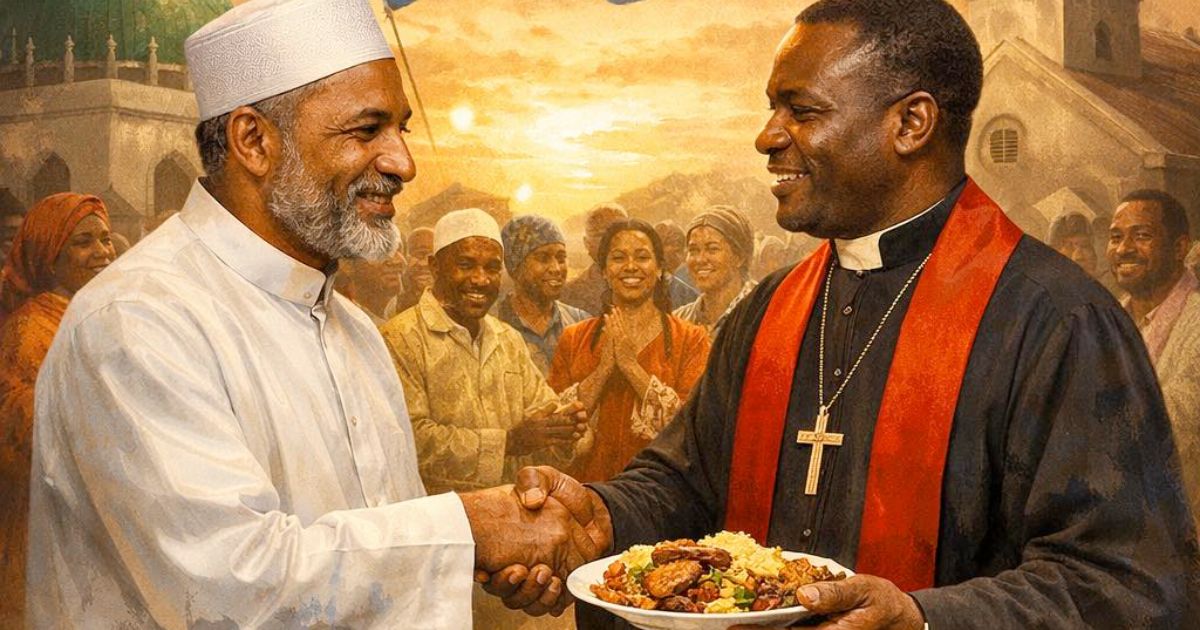

As religious guidance circulates online urging Muslims to reject food from Christians during festive seasons, constitutional law, Islamic theology, and Sierra Leone’s post war history all point in the opposite direction. At stake is not doctrine, but the moral responsibility of faith leaders in a plural society.

Sierra Leone is not merely a constitutional republic governed by written law. It is a moral community shaped by shared suffering, collective endurance, and an enduring belief that peaceful coexistence is indispensable to national survival. Its national identity has been forged not only through legal frameworks but through lived experience, particularly during and after a brutal civil war that tested the resilience of its social fabric and the moral imagination of its people.

The 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone enshrines freedom of religion, conscience, and association as fundamental rights. Section 24 affirms that “no person shall be hindered in the enjoyment of his freedom of conscience,” including freedom of thought, religion, belief, and the right to manifest religion in worship, teaching, practice, and observance.¹ These protections are not abstract ideals. They reflect the practical realities of a plural society whose cohesion depends on mutual respect, restraint, and social trust rather than religious isolation or exclusion.

In the aftermath of the civil war, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reinforced this constitutional vision. The Commission identified religious tolerance as one of Sierra Leone’s most effective social stabilisers during the conflict, noting that interfaith solidarity frequently shielded communities from deeper violence and social collapse. At the same time, it warned that sectarian rhetoric and absolutist preaching posed latent dangers to post war recovery, particularly in a society still healing from trauma. Religious leaders were therefore urged to act as custodians of peace, moderation, and reconciliation, mindful of the profound moral authority they wield over public attitudes and behaviour.

It is against this national and historical backdrop that concern has arisen over a recent video circulated online in which certain Islamic scholars in Sierra Leone reportedly advised Muslims not to accept food from Christians during the Christmas and New Year holidays. While presented as religious guidance, such counsel risks unsettling deeply rooted interfaith relationships and misrepresents both Islamic theology and Sierra Leone’s social history. More seriously, it conflicts with established Qur’anic principles, the Prophetic tradition, and Islam’s earliest encounters with Christianity.

Islam is not a faith of withdrawal, suspicion, or social severance. It is a faith of principled engagement rooted in moral clarity. The Qur’an situates human diversity within divine wisdom rather than fear or hostility. As stated in Surah Al Hujurat, “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you.” Difference, in this framing, is an invitation to understanding and ethical conduct, not a pretext for exclusion.

On the specific question of food, the Qur’an is unequivocal. Surah Al Maidah, Chapter 5 Verse 5, declares, “This day all good foods have been made lawful, and the food of those who were given the Scripture is lawful for you and your food is lawful for them.” Within Islamic jurisprudence, this verse establishes a clear and authoritative legal position. To prohibit what Allah has explicitly permitted is not an act of heightened devotion but a form of theological excess that classical scholars have consistently warned against.

Historical precedent reinforces this doctrinal clarity. When early Muslims faced persecution in Mecca, the Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, instructed a group of his followers to migrate to Abyssinia, present day Ethiopia. There they were received by the Christian ruler Al Najashi, who granted them protection, hospitality, and freedom of worship. Muslims lived under Christian care, shared food, and practised their faith openly, all with the Prophet’s full approval. This episode remains one of the clearest examples of interfaith solidarity in Islamic history.

The Qur’an further recognises the moral proximity between Muslims and Christians. Surah Al Maidah, Chapter 5 Verse 82, states, “And you will surely find the nearest of them in affection to the believers those who say, ‘We are Christians.’ That is because among them are priests and monks and because they are not arrogant.”This verse does not blur theological distinctions. Rather, it acknowledges ethical closeness rooted in humility, learning, and moral discipline.

Guidance on respectful engagement is elaborated further in Surah Al Ankabut, Chapter 29 Verse 46, which instructs Muslims to engage the People of the Scripture with wisdom and courtesy, affirming shared belief in one God while rejecting hostility and coercion.⁷ Likewise, Surah Al Mumtahanah, Chapter 60 Verse 8, explicitly permits kindness and justice towards those of other faiths who live peacefully alongside Muslims. Nowhere does the Qur’an justify social rejection through symbolic acts such as refusing food.

In Sierra Leone, interfaith coexistence has long been a social norm rather than a political slogan. Muslim families attend Christmas gatherings, Christian families participate in Eid celebrations, and meals are shared across religious lines. Condolences are exchanged without hesitation, and public ceremonies are jointly observed. This pattern reflects neither syncretism nor doctrinal compromise. It represents a culturally embedded ethic of neighbourliness that aligns fully with Islamic teaching and constitutional values alike.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission warned that absolutist religious narratives could destabilise fragile post conflict communities and undermine the delicate trust rebuilt after war. It urged faith leaders to exercise restraint, wisdom, and national responsibility in their public discourse. In this light, sermons or teachings that imply spiritual contamination through shared food are not only theologically weak but socially imprudent.

Islamic scholarship carries authority precisely because it claims grounding in knowledge. The Qur’an cautions against speaking without understanding. Surah Al Isra, Chapter 17 Verse 36, warns that hearing, sight, and the heart will all be held accountable. This places a moral burden on religious leaders to ensure that guidance is informed, balanced, and attentive to social consequence.

The Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, consistently modelled ethical pluralism. He accepted gifts from non Muslims, stood in respect for a Jewish funeral procession, and concluded treaties guaranteeing protection and autonomy for Christian communities and clergy. These actions were not political expedients. They were expressions of faith anchored in justice, mercy, and human dignity.

To preach Islam in Sierra Leone, therefore, is to preach peace, wisdom, and coexistence. The Constitution, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the Qur’an converge on a single principle: religious freedom must be exercised in a manner that strengthens social harmony rather than erodes it.

Sierra Leone’s interfaith harmony is not accidental. It is the product of historical wisdom, moral restraint, and shared sacrifice. Any interpretation of religion that threatens this harmony must be addressed calmly, knowledgeably, and firmly through education rather than alarmism.

Islam is a religion of peace, not by slogan but by scripture, history, and moral intent. Those entrusted with its message bear a responsibility to ensure that their words heal rather than divide, enlighten rather than inflame, and reflect the Qur’anic call to shared humanity.

FOOTNOTES

Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, Section 24.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone, Final Report, Volume Two, Chapter Three.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Hujurat 49:13, Sahih International translation.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Maidah 5:5, Sahih International translation.

Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasul Allah, account of the First Migration to Abyssinia.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Maidah 5:82, Sahih International translation.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Ankabut 29:46, Sahih International translation.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Mumtahanah 60:8, Sahih International translation.

Alie, Joe A D, A New History of Sierra Leone, on interreligious coexistence.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Sierra Leone, Final Report, Volume Three, Recommendations.

The Holy Qur’an, Surah Al Isra 17:36, Sahih International translation.

Muhammad Hamidullah, The Muslim Conduct of State, on treaties and interfaith relations.

Well, they have the freedom to refuse. It’s not compulsory. True Christians also share the same principles of not celebrating moslem holidays. We can all agree to disagree and life goes on.