In the political realm, the decision of an elected Member of Parliament (MP) to boycott his or her role carries significant implications. This matter can be viewed through the lens of an Equity Maxim which states that equity aids the vigilant, not the indolent, essentially meaning that one must actively utilize one’s rights and not neglect them.

Once elected, it is the duty of every MP in Sierra Leone to take the Oath of Office before officially assuming his or her position in Parliament as per Section 83 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991 (Act No 6 of 1991). This Oath, detailed in the Third Schedule, firmly requires MPs to pledge their loyalty to the Republic of Sierra Leone, and not to any specific political party.

There are also stipulated conditions under which an MP may be forced to vacate his or her seat, as detailed in Section 77(a)-(n) of the Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991. One may wonder, though, how a boycott by a political party might impact Parliament’s operations.

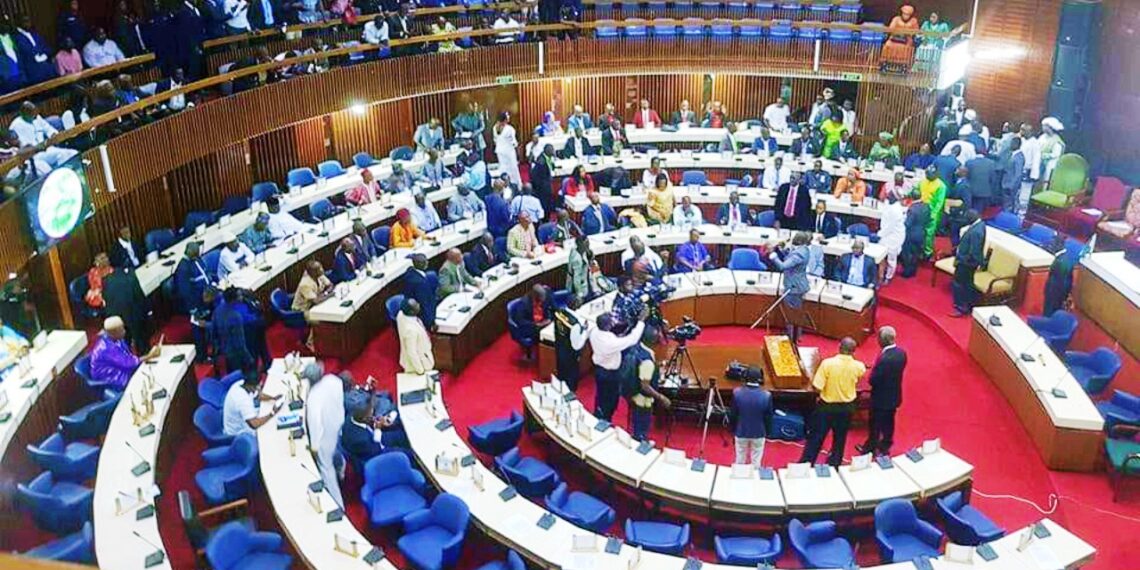

The Standing Orders of the Sierra Leone Parliament clarify that the required quorum for the House is one-fourth of the total number of Parliamentarians. Given the current distribution of seats (SLPP 81, APC 54, PCMP 14, for a total of 149), this means that the quorum is roughly 37 members. Therefore, the combined SLPP MPs and PCMP far exceed the necessary quorum, and any decisions made by the House after the Oath and Induction on July 12th and 13th are deemed legitimate.

But what of the fate of an MP-elect who does not take the Oath of Office? According to the Standing Orders, any member who is absent from Parliament without good cause for an aggregate of thirty days must vacate his or her seat. A “good cause” is identified as a reasonable excuse supported by evidence. However, to qualify for a “good cause”, an MP must have already taken the Oath of Office.

In the event of a blatant refusal to take the Oath of Office, it could be inferred after thirty days that the MP-elect is not willing to serve the people who elected him or her. This refusal could be deemed an unreasonable excuse, leading to the loss of the MP’s seat. As the saying goes, “A word to the wise is enough,” and the aforementioned potential consequences should not be taken lightly.

Cognizance must be taken that the repercussions of boycotting Parliament after being elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) have come to light. The boycott not only diminishes representation for constituents who elected the boycotting MP but also disrupts the legislative process, weakens the opposition, and strains party dynamics.

Moreover, the boycott of Parliament can significantly hinder the effectiveness of the legislative process. When a political party opts to boycott, it disrupts the smooth functioning of Parliament, causing delays in passing important legislation, impeding debates on critical issues, and hampering the ability to hold the Government accountable. The absence of boycotting MPs weakens the power of Parliament as a check on Executive authority.

By also boycotting Parliament, MPs forfeit their opportunity to shape policy and contribute to decision-making processes. They lose the chance to advocate for their constituents, raise concerns, and propose amendments to bills. This diminishes their influence and weakens their ability to bring about meaningful change.

Additionally, if the boycott is carried out by opposition MPs, it can lead to a reduced presence of the opposition in Parliament, creating an imbalance of power and potentially limiting robust scrutiny and accountability.

Furthermore, boycotting Parliament may trigger legal and constitutional provisions that address absenteeism and the consequences of failing to fulfill parliamentary duties. Such provisions can result in sanctions, loss of privileges, or even the vacating of the MP’s seat. The boycott thus carries significant legal and constitutional implications.

Lastly, the boycott can strain intra-party relationships and create divisions within the political party. It may lead to internal conflicts, loss of cohesion, and a weakened party structure. These dynamics can have long-term implications for the party’s ability to function effectively and achieve its political goals.

In summary, boycotting Parliament after being elected as an MP has wide-ranging ramifications that undermine democracy, weaken representation, dilute opposition, create disillusionment among constituents, carry legal and constitutional implications, and strain party dynamics. These consequences hinder democratic processes, impede progress, and erode public trust in the boycotting MPs and their political party.

5 Comments

5 Comments

No amount of threat would work!!!

I hope the APC MP have their reasons for not attending and also we elect them for good democracy not rigid democracy. The APC MP want the right thing be done and also Sierra Leoneans need social Justice.

There are several potential reasons why the main opposition might boycott a sitting government:

1. Lack of legitimacy: The opposition may refuse to participate in a government that they believe is not legitimate or that they view as having come to power through fraudulent or unfair means. This could include allegations of electoral fraud or irregularities in the electoral process.

2. Disagreements on policy: The opposition may have significant policy disagreements with the ruling government and may choose to boycott in order to signal their opposition and refusal to endorse or support policies they disagree with. This can be particularly true if the opposition believes that their participation in government would not lead to meaningful policy change or that their concerns would not be adequately addressed.

3. Lack of representation: The opposition may feel that they are not adequately represented in the government or that their viewpoints and constituents are not being properly heard or considered. This could be due to a lack of proportional representation or a belief that the government is primarily serving the interests of a particular group or constituency.

4. Lack of trust: The opposition may have a lack of trust in the ruling government and may believe that participating in the government would not result in meaningful change or that their concerns would not be taken seriously. This could be due to past experiences of broken promises or a belief that the ruling government is not genuinely interested in working with the opposition.

5. Strategic reasons: The opposition may boycott as a strategy to exert pressure on the ruling government or to gain leverage in negotiations. By refusing to participate, the opposition can demonstrate their dissent and potentially force the government to address their concerns or engage in dialogue.

Overall, the decision to boycott a sitting government is typically driven by a combination of factors, including a lack of legitimacy, policy disagreements, lack of representation, lack of trust, and strategic considerations.

ent and call for mass protests. They claim that the election was not conducted fairly and accuse the sitting government of manipulating the results in their favor. The main opposition party believes that participating in a rigged parliament would only legitimize the government’s actions and undermine the democratic process.

As a result, the main opposition party decides to boycott the parliament and refuse to take any seats they may have been allocated. They argue that by not participating, they can send a strong message to both the government and the international community that they do not recognize the legitimacy of the election outcome. Boycotting the parliament also allows them to gather support from their followers and mobilize mass protests to demand a fair and transparent re-election.

The opposition party hopes that by boycotting the parliament, they can exert enough pressure on the sitting government to hold new elections under independent supervision to ensure a fair and democratic process. They argue that it is their responsibility to stand up for the rights of the people and work towards a system that truly represents the will of the citizens.

However, boycotting the parliament also comes with risks. The opposition will forfeit their ability to influence decision-making and hold the government accountable from within the legislative body. It may give the sitting government even more power and make it more difficult for the opposition’s voice to be heard.

Ultimately, the decision to boycott the parliament and call for mass protests is a strategic move by the main opposition party to challenge the legitimacy of the sitting government and push for a fair and transparent election process. The success of their boycott and protests will depend on their ability to gather public support, both nationally and internationally, as well as the government’s response to their demands.

All I am praying for is for APC to please stand on their words and don’t go to parliament or council. Gento will be the mayor of freetown and SLPP councillors will be be all over the country. Maybe this is God want to answer our prayers so that God remove the bad eggs and bless this country.

Please APC be a man enough. Don’t go anywhere.