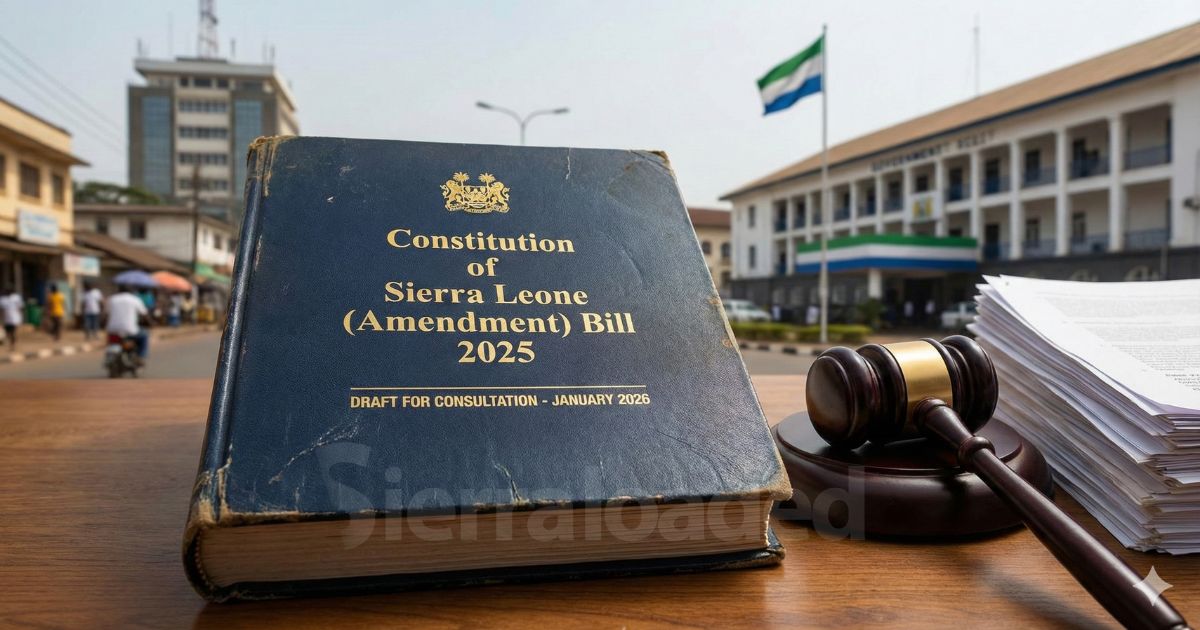

Early January has reignited a familiar yet unsettling national debate: Sierra Leone is once again drafting a new constitution. On the surface, constitutional reform sounds progressive, even overdue. But beneath the rhetoric lies a deeper question that citizens must not shy away from asking: why now, and to whose benefit?

The current move seeks to replace the 1991 multiparty constitution, a document crafted under the government of the late President Joseph Saidu Momoh. At the time of its adoption, the 1991 constitution was widely celebrated. It marked a decisive break from the 1978 One-Party Constitution imposed under President Siaka Stevens and promised a return to pluralism, political competition, and democratic governance.

Crucially, the 1991 constitution opened the political space by allowing multiple parties to contest elections under the supervision of an independent electoral system. In the context of late 20th-century Sierra Leone, this was monumental. It paved the way for parties such as the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) and the United National People’s Party (UNPP) to participate in the 1996 elections. That election would eventually usher in Ahmad Tejan Kabbah as president, following a narrow victory over the UNPP’s John Karefa Smart (Kabbah secured 59.4% after a runoff).

For years, Sierra Leone functioned, albeit imperfectly, under the framework of the 1991 constitution. That relative stability began to fray during the administration of Ernest Bai Koroma of the All People’s Congress (APC). Responding to mounting criticism, his government called for the review, repeal, or replacement of certain constitutional provisions. Koroma’s administration argued that the 1991 Constitution had become outdated and unfit for a modern democracy. They propounded it failed to reflect the realities of a post-war country like excessive power in the presidency, improper accountability and emerging democratic norms.

To address these concerns, the APC government established the Justice Cowan Constitutional Review Committee (CRC). The Commission embarked on nationwide public consultations, engaging citizens across districts and collecting submissions from civil society groups, traditional leaders, and political stakeholders. Some of the key recommendations included: Chapter II, Section 14 (Fundamental Principles of State Policy), curtailing the powers of the President as the Supreme Executive Authority and maintaining the 55% threshold for presidential elections. Also, the CRC recommended the separation of the Office of the Attorney-General from the Minister of Justice and for the constitution to grant more freedom to the press.

Yet even then, suspicion loomed. Rumours circulated that President Koroma intended to use constitutional reform as a pathway to secure a third term in office. A close source once confided that the proposal was nearly tabled in Parliament, only to be blocked by some senior APC parliamentarians who refused to support it. That story deserves its own examination on another day. For now, the focus must remain on the constitution itself.

When the APC government was voted out in 2018 and replaced by Julius Maada Bio and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), constitutional reform all but disappeared from public discourse. Throughout Bio’s first term, the matter received little attention (at least publicly). If work was ongoing, it was done behind closed doors. Most Sierra Leoneans remained unaware of any serious progress until late 2025 spilling into 2026.

This renewed push for a new constitution uncannily mirrors the timing and circumstances of the Ernest Bai Koroma era. It raises uncomfortable but necessary questions. Why is the Bio administration suddenly expending significant political energy on constitutional enactment with less than three years left in its tenure? Why is there a pronounced emphasis on introducing new election-related provisions rather than addressing long-standing governance and accountability gaps? The Sierra Leone government is currently seeking a new constitution with election-related provisions like reducing the threshold from 55% to 50% plus one vote, adoption of the Proportional Representation (PR system).

On a positive note, the new constitution could have a provision supporting independent candidates to contest for presidential election and how removal of a sitting president and vice from a political party to follow a constitutional due-process. This could appease former Vice President, Samuel Sam-Sumana more than anyone else. In lucid terms, Sam-Sumana would have survived as the Vice-President even if the APC would have removed him.

Prominent critics have begun to voice these concerns. Basita Michael, for instance, has questioned the government’s approach, particularly the apparent lack of broad-based citizen participation in the drafting process. According to Michael, the review process has been “slow, opaque, and at risk of being manipulated by political interests rather than genuinely reflecting the will of the people. Also, Vicky Remoe has echoed similar reservations, taking to X to express her unease. In her post, she argued that the pace of the review is moving too quickly and that could leave the voice of the citizens excluded from the process. Her call captures the need for transparency, patience and genuine democratic participation in amending the constitution.

As a journalist and citizen of Sierra Leone, I find myself compelled to align with these concerns. We are repeatedly told that this constitutional process is merely the continuation of work initiated by the previous APC government. But we must pause and reflect: wasn’t poor governance and questionable decision-making precisely why Sierra Leoneans voted for change in 2018? Must a new government inherit not just projects, but also flawed approaches?

More troubling still is the narrow focus on electoral provisions. Are elections the most urgent constitutional issue facing Sierra Leone today? Why does the government continue to sidestep critical recommendations outlined in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report? Why are accountability, decentralisation, and social justice perpetually relegated to the margins?

If citizens do not begin to question authorities, without bias, without fear, and without political favour, we will continue to be taken for granted. Democracy does not thrive on silence or blind loyalty; it survives on scrutiny.

This is my two cents. Posterity will judge whether I was right, but it will not be said that I was silent. I rest my case.

Well inked bro