Joseph Fitzgerald Kamara, Counsel representing Former President Ernest Bai Koroma in the Appeal Court challenge against the Government White Paper recommendations on the Commission of Inquiry has filed an application before the three Appeal Court Judges in a move to take his client’s matter to the Supreme Court for interpretations.

Earlier last week, the defence Lawyer representing the former President had intimated the Appeal Court Judges that he would be moving an application to be granted leave to seek the interpretation of the Supreme Court on the issue of immunity of the former President.

Lawyer J. F. Kamara said “We are now seeking by notice of motion application reference to the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone Pursuant to Section 124(1)(a) and Section 124(2) of the 1991 Constitution.”

He said the case reference is by way of interpretation of section 48(4) of the Constitution, adding that they are also seeking interpretation of Section 147 of the 1991 Constitution.

He said “My Lords the Appellant also seeks an interpretation to determine what Constitute proceedings under Section 48(4).

It is our submission that the issue of interpretation of Section 48(4) have been barely examined by the Supreme Court. And in the event where it has done so it has been limited in scope.

Lawyer Kamara said there is no point in time in the jurisprudence of this country that the issue of civil or criminal proceeding being instituted against a former head of state to examine decisions that they took while in office.

He maintained that a former President of the Republic of Sierra Leone cannot be subjected to civil or criminal proceeding for executive decisions taken while in office, adding that the current case deals with post office decision that was taken by the former President.

The Appeal Court Judges, Justice Alhaji Momoh Jah Stevens, Justice Adrian Fisher, and Justice Ivan Sesay through their Registrar has adjourned the matter to Wednesday for the counsel for the State Lawyer Robert Kowa to reply.

COI. APP. 40/2020 2020 NO.

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF SIERRA LEONE

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 48(4)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTIONS 53(1) (2) &(3)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 108(7), 124(1)(a)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 147-150, 171(15)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT NO.67 OF 2018

(HON. WILLIAM ANNAN ATUGUBA COMMISSION OF INQUIRY)

BETWEEN:

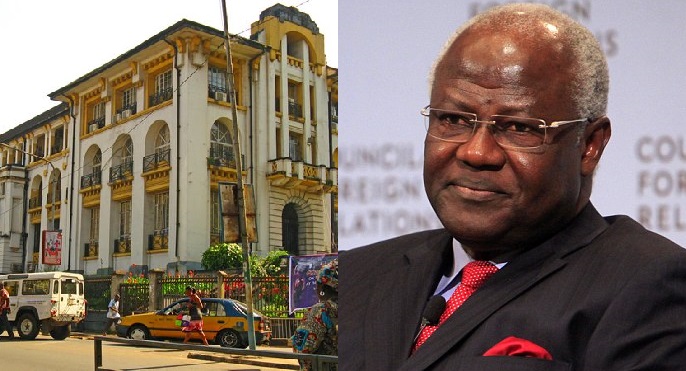

DR. ERNEST BAI KOROMAAPPELLANT/APPLICANT

RO-BURREH HOUSE

TEKO

MAKENI CITY

AND

ATTORNEY-GENERAL & MINISTER OF JUSTICE- RESPONDENT

LAW OFFICERS DEPARTMENT

GUMA BUILDING

LAMINA SANKOH STREET

FREETOWN

NOTICE OF APPLICATION SEEKING REFERENCE TO THE SUPREME COURT, PURSUANT TO SECTION 124 (1)(a) & 124 (2) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991 FOR AN INTERPRETATION OF SECTION 48(4); 147, 148(a)(b), and 149(4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, ACT NO. 6 OF 1991 AND THE SUPREME COURT RULES, 1982, STATUTORY INSTRUMENT NO. 1 OF 1982, RULE 99

INTRODUCTION:

1. The former President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, now Appellant in the matter of Dr Ernest Bai Koroma vs. Attorney-General and Minister of Justice, seeks a case reference to the Supreme Court by way of interpretation of Section 48(4), 147, 148(a)(b) and 149 of the Constitution, to determine scope, function and relationship; and on a true and proper construction, to determine the meaning and what constitutes the term ‘Proceedings’ under section 48(4).

2. More particularly, whether to subject a former President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, to Commission of Inquiry proceedings, for executive decisions taken while holding office, without the express waiver of Parliament is valid and efficacious in law. If answered in the negative, whether that renders a breach of section 48(4) and therefore null and void and ultra vires the Constitution.

3. Similarly, the other question for determination by the Supreme Court, is whether sections 147-149 of the Constitution, are to be read conjunctively and with contemplation to the provisions of section 48(4).

4. To a large extent, these are novel points of law and if argued, barely on the periphery; or examined before the Supreme Court, without any definitive pronouncement. The Supreme Court has been given exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and interpretation involves determining the scope of provisions and discovering the intent of the framers of the Constitution.

5. While there is judicial precedent showing that the provision of Section 48(4) is clear and unambiguous (See AHMED TEJAN KABBA vs. FIRETEX COMPANY (SL) LTD CIV.APP76/95), yet, the Presiding Judge, the Hon. Justice Gelaga-King, thought it fit for constitutional interpretation by way of a case reference to the Supreme Court. Being in the minority, the Case Reference was never pursued to the Supreme Court.

6. The Hon. Justice A.B. Timbo, JA, (as he then was)in the same case above, opined that “all that section 48(4) of the Constitution has done is to confer immunity on the Head of State, whilst he holds that office, against criminal or civil process in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by him whether in his official or private capacity”. Regrettably, but with respect, the above statement is just a recital of the section, with no explanation as to the scope or true meaning of the terms as applied in the section.

7. Conversely, where the provision of a section of the Constitution, on its face, appear to be clear, and unambiguous, the Court of Appeal, may still refer the case to the Supreme Court, where it considers it necessary to do so. The case of JAMES ALLIE AND OTHERS vs. THE STATE (SC Misc. App. No. 3/81) is illustrative in support of this proposition. In that case, the provisions regarding the right of appeal from the Court of Appeal to the Supreme Court, would at first glance, appear clear and unambiguous, yet the Court of Appeal sua moto referred to the Supreme Court, despite Counsel’s withdrawal and abandonment of the argument. The Supreme Court, acceded that indeed the circumstances warrant a case reference notwithstanding the appearance of a clear and unambiguous characterization of the words of the provision.

8. Interestingly also, the Supreme Court in the case of JOHN OPONJO BENJAMIN AND OTHERS vs. DR CHRISTIANA THORPE AND OTHERS, SC NO.4/2012, while generally acknowledging Presidential Immunity within section 48(4), posited that it cannot be extended to ‘Election petition’ against an incumbent. Per Valesius Thomas, JSC, quoting with approval OBIH VS. MBAKWE (1984) 1 SCNLR)192 .

9. In the case of ZOUZOUKI DEGUI VS THE STATE (1981) (COURT OF APPEALS REFERENCE NO.1 OF 1981), the Supreme Court acceded to a Case Reference from the Court of Appeal on Interpretation of the powers of the Attorney-General and Minister of Justice, and held that the Director of Public Prosecutions was not competent to give the consent and certificate required by section 53(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act 1965.

10. Another case worthy of note, is the Case Reference in the matter of ALL PEOPLES CONGRESS VS NASMOS MISC. APP. 4/96 the Reference was acceded to by the Supreme Court, when dealing with the interpretation of section 133(1) of the Constitution relating to claims against the Government.

11. In the light of the foregoing, judicial precedent is replete with Case References to the Supreme Court for interpretation, and for which, the substantive proceedings at the Court of Appeal, were stayed, awaiting the disposition of the case in accordance with the decision of the Supreme Court.

12. Inarguably, not all constitutional questions may necessarily involve or entail the interpretation of the Constitution. (see WELLINGTON DISTILLERIES VS. ECTRODIA P. CLARKSON MISC. APP. NO.4/1981. How then, have the Courts over the years, determined an Interpretation issue of the Constitution?

Legitimate Forensic Test:

13. An issue of enforcement or interpretation of a provision of the constitution arises-

(i) where the words of the provision are imprecise or unclear or ambiguous. Put another way, it arises if one party invites the court to declare that the words of the section have a double-meaning or are obscure or else mean something different from or more than what they say;

(ii) where the rival meanings have been placed by litigants on the words of any provision of the Constitution (See Question3-Case Reference herein)

(iii) where there is a conflict in the meaning and effect of two or more sections of the Constitution, and the question is raised as to which provision should prevail (See Question 2 & 5 Case Reference herein)

(iv) where on the face of the provisions, there is a conflict between the operation of particular institutions set up under the Constitution, and thereby raising problems of enforcement and of interpretation (Office of the Presidency vs Commission of Inquiry-Questions 1,2,3,4,5 & 11 Case Reference herein).

(See ADUAMOA II V. TWUM II (2000) SCGLR165 ANIN JA (1980) GLR AT 605)

14. The Respondent herein, that is the State, filed a response to the Appellant’s Synopsis, which strengthens and canvasses the argument that the issue of immunity is one of interpretation, worthy of a case reference to the Supreme Court. At page 3, of their Response, it is stated, “that the Appellant’s appeal dealing with the immunity provisions of Section 48(4) of the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone, may amount to a question of an interpretation of the provision of the said Constitution”.

15. The use of the word ‘may’ by the State, introduces the element of a possibility, making way for an amount of uncertainty. And indeed, where the State/Respondent herein, is visibly uncertain on the state of the law, and goes on to hold diametrically opposed views on the same issue at page 4, paragraphs 1 through 4 of their Response, nothing more in addition to the foregoing discourse, could give rise to a Case Reference to the Supreme Court. Such, will undoubtedly resolve the conflict over the immunity issue and put to rest a very vexed or problematic question.

– QUESTIONS FOR INTERPRETATION BY THE SUPREME COURT

1. Whether Section 147 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone, 1991, Act, No. 6 of 1991 (“Constitution”), should be read in conjunction with Section 48(4) of the Constitution? If the answer is in the affirmative, what effect would that have on a former President for executive decisions taken while holding office;

2. Whether the exercise of powers conferred under Constitutional provisions of section 147 exercised in non-compliance of section 48(4) of the Constitution, render the exercise of that power a nullity/nugatory and ultra vires the Constitution, having regard to the peculiar circumstances of this case?

3. Whether Section 148(1)(a) and (b) of the Constitution, that is to say, enforcing the attendance of witnesses, examining them on oath, affirmation or otherwise; and compelling the production of documents; amount to ‘proceedings’ as contemplated under Section 48(4) of the Constitution.

4. In the light of Questions 1, 2 and 3 posed supra, can it be said that section 149(4) of the Constitution, which provides that a Commission of Inquiry making ‘an adverse finding against any person, resulting in penalty, forfeiture or loss of status, ‘for purposes of this Constitution’ be deemed a judgement of the High Court of Justice’; is an outcome borne out of ‘proceedings’ as contemplated in section 48(4)? If the answer to the question is yes, does that render a breach of section 48(4) and therefore null and void and ultra vires the Constitution?

5. Whether section 4 of Constitutional Instrument No.67 of 2018, expressly or by necessary implication, conflict with section 48(4) of the Constitution? If the question is answered in the affirmative, does that fact render the impugned provision null and void, and ultra vires the Constitution?

6.On a true and proper construction of Constitutional provisions of section 48(4), whether a President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, is vested with Presidential immunity; If the answer to this question is in the affirmative, can the immunity be characterized as personal or functional, or both;

7. Whether Presidential immunity, is extended to cover executive decisions ONLY during the currency of the term of Office of the President; or is it in continuum, that is, the immunity continues in respect of those executive decisions while in office, even after he or she has vacated the Presidency?

8. In the event the first limb to Question 2 is answered in the restrictive sense, is it the position that a former President upon vacating office, is exposed to civil or criminal proceedings for executive decisions while holding office?

9. In the alternative, should the second limb to Question 2 be answered in the affirmative, that is to say, the immunity continues even after vacating the Office of President, can it then be said, that such immunity is absolute or subject to limitation?

10. In the light of Question 4, whether ‘immunity’ continues after a president has vacated office, is it that such immunity is limited and subject to Parliamentary Waiver? Can it then be said that under section 48(4) of the Constitution, Parliament confers immunity while a person holds or performs the functions of the Office of President and by necessary implication ONLY PARLIAMENT can waive that immunity in express and unequivocal terms?

11. On a true and proper construction of Section 48(4) of the Constitution, can it be said, that to subject a former President of the Republic of Sierra Leone, to Commission of Inquiry proceedings, for conduct during his tenure of office, without the express waiver by Resolution of Parliament, renders a breach of section 48(4) and therefore null and void and ultra vires the Constitution?

AND that the proceedings in the instant Action of

Dr. Ernest Bai Koroma vs. Attorney-General & Minister of Justice be stayed pending the reference to the Supreme Court by way of a Case Stated by this Honorable Court pursuant to the Supreme Court Rules, 1982, Statutory Instrument No. 1 of 1982, Rule 99

Joseph Fitzgerald Kamara, Esq.

JFK & PARTNERS,

SOLICITORS FOR THE APPELLANTS

Dated this day of July 2021.

TO:

1. The Registrar, Court of Appeal

The Honorable Justice Ivan Sesay, JA.

The Honorable Justice Momoh-Jah Stevens, JA

The Honorable Justice Adrian Fisher, J.

2. Attorney-General & Minister of Justice

Law Officers Department

Guma Building

Lamina Sankoh Street

Freetown

THIS NOTICE IS FILED BY JFK & PARTNERS THIS DAY OF ….JULY 2021, AND WHOSE ADDRESS FOR SERVICE IS 42 BATHURST STREET, FREETOWN, FOR AND ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLENT HEREIN.

COI. APP. 40/2021 2020 NO.

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF SIERRA LEONE

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 48(4)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTIONS 53(1) (2) &(3)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 108(7), 124(1)(a)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991, ACT NO.6 OF 1991, SECTION 147-150, 171(15)

AND

IN THE MATTER OF CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT NO.67 OF 2018

(HON. WILLIAM ANNAN ATUGUBA COMMISSION OF INQUIRY)

BETWEEN:

DR. ERNEST BAI KOROMA APPELLANT/APPLICANT

RO-BURREH HOUSE

TEKO

MAKENI CITY

AND

ATTORNEY-GENERAL & MINISTER OF JUSTICE- RESPONDENT

LAW OFFICERS DEPARTMENT

GUMA BUILDING

LAMINA SANKOH STREET

FREETOWN

______________________________________________

NOTICE

________________________________________

JFK & PARTNERS

42 BATHURST STREET

FREETOWN,

SOLICITORS FOR THE APPELLANTS

1