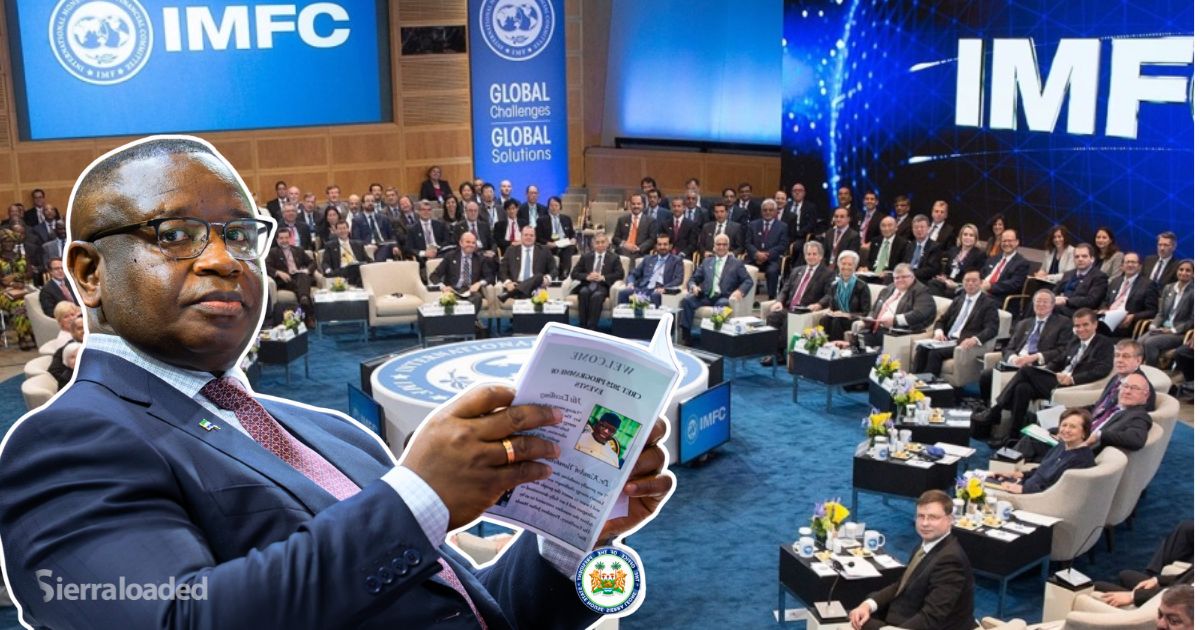

On December 16, 2025, the Sierra Leone government released a celebratory press statement. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) completed its latest review of the country’s economy, unlocking an immediate payout of $79.8 million to the people of Sierra Leone.

The tone from Ahmed Sheku Fantamadi Bangura, the Minister of Finance, was triumphant. He spoke of “macroeconomic stability,” a projected 4.4% growth for the coming year, and a decline in inflation. To the officials in Freetown, this money is a lifeline—a sign that the international community trusts the leadership of President Julius Maada Bio. But if you look past the press release and walk the streets, a very different, more painful picture emerges.

We are witnessing a collision between two realities. One is the official narrative of “fiscal discipline” and “resilience.” The other is the harsh daily grind of the average citizen. As we stand here in late 2025, Sierra Leone is trapped in a cycle that started 64 years ago at independence. We ask for help, we receive loans, we celebrate the cash, and then we struggle to pay the interest while our schools and hospitals crumble. It is time to ask why a nation so rich in resources is still celebrating debt as if it were income.

The government views this recent $79.8 million as a buffer to support social services and infrastructure. They argue that their tight control over spending has stabilised the Leone and lowered borrowing costs. However, this “stability” feels like an illusion when measured against the cold, hard data.

While the government points to future growth, the reality on the ground is that national debt has swollen to 78% of our GDP. To put it simply, every man, woman, and child in Sierra Leone effectively owes foreign creditors about $500. For a family struggling to buy a bag of rice—which has seen prices jump 30% recently—that burden is terrifying.

The consequences of this reliance are visible everywhere. When a country relies on the IMF to keep the lights on, it loses the freedom to decide its own future. The IMF often demands cuts in public spending to ensure debts are repaid. This is likely why, despite the loans, we see a health system where life expectancy is stuck at just 54 years, and malaria still kills *7,000 people annually.

This is also why we have a youth unemployment crisis affecting 1.5 million young people. We are borrowing money to plug holes in a sinking ship instead of building a new boat. The foreign reserves we do have cover less than two months of imports, meaning we are always just a few weeks away from a total economic shutdown if the next loan doesn’t come through.

So, how do we stop this?

How does Sierra Leone break a habit that has lasted over six decades? The answer lies in looking at our neighbours who have managed to change their story. We must stop thinking that “aid” is the solution and start realising that “production” is the only way out.

First, we need to get serious about “local content” and value addition. Look at Botswana. Like us, they have diamonds. But decades ago, they decided not just to dig them up and ship them out. They insisted that processing, cutting, and polishing take place within their country. This kept the wealth and the jobs at home.

In contrast, Sierra Leone exports raw wealth and imports expensive finished goods. We need strict laws that force mining and agricultural companies to process their goods here. If we grow cocoa, we should be exporting chocolate, not just beans. If we mine iron ore, we should be looking toward steel production, not just shipping dirt.

Second, we must empower local entrepreneurs to fix our trade imbalance. Currently, we import almost everything, which drains our foreign currency and weakens the Leone. We can look to Rwanda as a reference point. Rwanda isn’t rich in resources, yet it has maintained steady growth by making it incredibly easy to start a business and aggressively promoting “Made in Rwanda” products.

Rwanda cut red tape and corruption—areas where Sierra Leone is struggling, currently ranking 108th out of 180 on the Corruption Perceptions Index. If we supported our own small businesses with the same enthusiasm we show for foreign investors, we could produce our own food and clothes. This would keep our money circulating inside the country rather than sending it to China, Europe, or the Middle East.

Finally, we need to fix our agriculture to ensure food security. It is embarrassing that a fertile nation like ours spends millions of dollars importing rice. Countries like Ethiopia have invested heavily in industrial parks and modern agriculture to boost exports. We have the land and the rain. We need to move beyond subsistence farming to large-scale production run by Sierra Leoneans. This doesn’t just feed us; it lowers inflation naturally because we aren’t buying food with weak local currency.

The recent government press release praises the “Big 5” game changers, but real change doesn’t come from a bank transfer in Washington, D.C. It comes from the sweat and innovation of local people. My own proposal to reform mining to add 100,000 jobs is the kind of concrete thinking we need, rather than vague promises of “inclusive growth.”

The celebration of the December 16th disbursement is understandable—governments need cash to operate. But it should be a sombre moment, not a party. It is a reminder that 64 years after independence, we still cannot pay our own bills.

The path to financial freedom is not paved with more loans. It is paved with factories in Bo, rice farms in Kambia, and tech startups in Freetown. Until we produce what we consume and process what we export, we will remain servants to our lenders, forever waiting for the following press release to tell us we have survived another year.