Twenty-five years ago, Sierra Leone was plunged into unimaginable chaos. Freetown, our beloved capital, was in flames. It was a day of horror, grief, and despair as the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) and renegade soldiers of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) unleashed a reign of terror on innocent civilians.

Lives were shattered, homes burned to ashes, and hope seemed extinguished.

I was just a little boy then, yet old enough to remember every haunting detail of that fateful morning. It was Wednesday, January 6, 1999, just another day of fasting during Ramadan. We were to start the 18th day of fasting that morning. I still recall the peace with which we went to bed, unaware of the storm about to break loose. Around 2 a.m., noises erupted from the neighborhood, jolting us from our sleep. At first, I thought it was time for the early morning meal, “Sokoli.” But instead of the comforting aroma of food, we were greeted by chaos and panic.

Fear swept through the house. In the confusion, my family was torn apart. My father and some relatives decided to head east, while my younger brother Bobson, our cousins Abu and Mohamed Fofanah, and I ventured west, as I convinced them to head to the direction where my mother stayed at Regent Road in central Freetown. It was an ECOMOG controlled area.

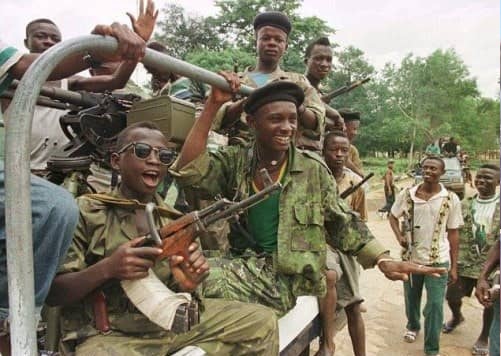

The streets were unrecognizable. Crowds of frightened civilians thronged the roads, their faces etched with terror. As we moved towards Black Hall Road, we encountered something that froze my blood; hidden among us were rebels. Children as young as ten wielded AK-47s that seemed too heavy for their frail bodies, yet their eyes glimmered with a cold, detached brutality.

Near Manfred Lane, a young boy, no older than ten, emerged as the leader of a group of rebels. He yelled at us, accusing us of siding with ECOMOG, the foreign peacekeepers. Abu tried to calm him, pleading that we were only trying to find safety. A more mature rebel intervened, leading us to a side street. There, he lectured us on loyalty, accusing us of trusting foreigners over our “brothers.”

Gunfire echoed all around. The streets were rivers of blood, and the air was heavy with smoke and the cries of the dying. We stumbled through the chaos, eventually reaching ECOMOG-controlled areas. But safety was an illusion. ECOMOG, overwhelmed by the situation, struggled to distinguish between rebels and civilians. Innocent people were summarily executed on mere suspicion. I watched in horror as a young boy, barely twelve, was gunned down at point-blank range on Lightfoot Boston Street.

The word “collaborator” became a death sentence. Anyone accused of aiding the rebels was killed without trial. The paranoia was suffocating, and the fear of being labeled haunted every step we took. Realizing that even ECOMOG was no refuge, we decided to return to the east, preferring the devil we knew.

Back in the rebel-held area, survival became a delicate dance. We were forced to sing praises to the rebels, chanting, “Na wi broda dem, we want peace.” It was a song of submission, a desperate attempt to stay alive. Yet even amidst this charade, danger lurked at every corner. One morning, a child rebel demanded my toothbrush. When I hesitated, he slapped me so hard I momentarily lost hearing in one ear. Trembling with fear, I obeyed his every command, praying silently for mercy.

The final days of the siege brought relentless shelling. Alpha jets bombarded the city, and entire neighborhoods were reduced to rubble. My father decided we must flee across the Atlantic Ocean to Kambia District. At Big Wharf, chaos reigned as families scrambled to board wooden boats. In the madness, my father fell into the water. My heart stopped as I watched him struggle, unable to do anything but cry. He was rescued, and we were separated, he boarded one boat while I was forced onto another with others.

The journey across the Atlantic was a blur of fear and despair. We reached Tombowala, then walked to Tainbana, my stepmother’s village. Days later, we reunited with my father and family at Rosinor before returning to Freetown. But Freetown was no longer home. The city was a graveyard, its streets littered with corpses and ruins. Friends were gone, their lives stolen by senseless violence. Our neighborhood, Kissy Brook, was unrecognizable.

The memories of that day remain vivid, etched into my soul. The sound of gunfire, the smell of burning flesh, the sight of lifeless bodies, they haunt me still. January 6, 1999, was more than just a day of horror; it was a moment that changed us forever. It taught me the fragility of life and the resilience of the human spirit.

The scars of that day remain, not just on the city, but on my soul. The fear, the heartbreak, the helplessness, all of it lingers, an indelible mark on the boy I was and the man I became. January 6, 1999, was not just a day of war; it was a day of shattered innocence.

May we never forget the lives lost and the lessons learned? May we, as a nation, vow to never let such darkness consume us again? Let us forever prefer peace to anything that has the tendency to take us back to such experience.

It was really a dark day for this country. May God help us 🙏🙏

Amen

Amin to all your prayers, May there soul continue to rest in peace